Principles of passing and catching

This is an excerpt from Basketball Skills & Drills 4th Edition With HKPropel Online Video by Jerry V Krause,Craig Nelson.

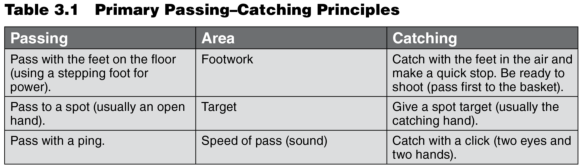

The overall goal of passing and catching is for both the passer and the catcher to produce passes that are on time and on target. Table 3.1 presents three key passing principles and three related catching principles.

Critical cue

Passes need to be on time and on target.

Players need to look for the pass before dribbling. When catching, players should follow the rim-post-action (RPA) rule: When they catch the ball within the operating area near the offensive basket, they should catch the ball and face the basket to look for the shot (rim or backboard spot), look to pass to a cutter in or near the post area or an inside post player (post), and then move the ball (action). A player's natural preference, or first instinct, however, is to dribble, which is an individual skill and thus tends to be practiced each time a player touches the ball. Overcoming this instinct requires continual emphasis on the shot and pass options.

Critical Cue

See the whole floor with big vision; look to pass first and dribble last.

Players can make good passes only when coaches teach the fundamental elements of passing, including the three passing rules:

- Footwork: Pass with the feet on the floor in most situations. Pass with a quick step for quickness and power (using the stepping foot). When possible, the catcher should catch the ball with the feet in the air. This is critical for avoiding traveling violations; when a player lands with a one-count quick stop, either foot can be used legally as a pivot (turning) foot.

- Target: Each pass must be thrown accurately to a spot target. The target is usually provided by the catcher in the form of a raised hand away from the defender. When possible, players should hold both arms up when catching—one to provide a target hand and the other to ward off the defender (figure 3.2). The catcher must give a spot target whenever possible.

Figure 3.2 Getting open: Keep both arms up.

- Speed of pass: The ball must be passed quickly, before the defender has time to react. The pass should be snappy and crisp—neither too hard nor too easy. A quick step is usually made in the direction of the pass to provide added force. The concept of passing with a ping was made popular by Fred “Tex” Winter, hall of fame coach and longtime assistant coach for the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers. The most important part of the successful pass and catch is the second part—the catch. Most of the time, the catcher should catch with a click (getting two hands on the ball). In contrast, if the ball is thrown too hard, it slaps loudly as it is caught; when thrown too softly, no sound is heard. A proper catch can be made in one of two ways: blocking with the outside spot hand and securing the ball with the other hand, or just getting two hands on the ball as soon as possible when catching it.

Here are three more passing recommendations.

- Timing: The ball must be delivered when the receiver is open—not before or after. Pass with a ping at the right time. When learning to pass, exaggerate the follow-through.

- Deception: The passer must use deception to confuse the defender, who is reading the passer (especially the eyes) and anticipating the pass. Use ball fakes and use vision to see the whole floor (big vision) while focusing on the spot target.

- Meeting the ball:Catchers should shorten all passes (i.e., run through the ball) by meeting or coming toward the ball. (This does not apply, of course, on a breakaway, in which the player moves to the basket ahead of the defense.)

Passers should visually locate all teammates and defenders—seeing the rim of the basket when in the frontcourt and the net when in backcourt—while concentrating on the potential receiver without staring. This awareness can best be achieved by surveying the whole floor area (using big vision) with the ball in triple-threat position. When catching a pass, players should always be prepared to shoot (catch the ball and face the basket) if open and within range; if unable to shoot, they should try to pass to an open teammate before dribbling (rim-post-action).

Players must learn to give up the ball unselfishly by passing to an open player. Ball handlers can also dribble-drive and pass (i.e., penetrate and pitch)—that is, create assist opportunities by making dribble moves to the basket that allow them to pass to open teammates who can then score. When players are passing, they should choose to make the easy pass through or by the defender. Coaches should teach players not to gamble on passes; they should be clever but not fancy. Most of the time, a player making a dribble drive should use a quick stop before passing the ball at the end of the penetration or drive, staying under control (maintaining balance) and avoiding the offensive charge. This technique applies the rule of passing and stopping with the feet on the floor. John Stockton, all-star guard for Gonzaga University and the Utah Jazz, became the all-time assist leader in the NBA by making the easy pass (i.e., the simple play). His counterpart at Gonzaga, Courtney Vandersloot, a first team All-American and WNBA all-star was also an unselfish passer known for making the simple play.

Critical Cue

Make the easy pass.

More Excerpts From Basketball Skills & Drills 4th Edition With HKPropel Online VideoSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- Using double inclinometers to assess cervical flexion

- Trunk flexion manual muscle testing

- Using a goniometer to assess shoulder horizontal adduction

- Assessing shoulder flexion with manual muscle testing

- Sample mental health lesson plan of a skills-based approach

- Sample assessment worksheet for the skill of accessing valid and reliable resources