Changes to bone formation during menopause

This is an excerpt from Yoga for Menopause and Beyond epub by Niamh Daly.

A) BONES

The changing biology

Essentially, bone formation (osteogenesis) occurs when the osteoblasts that lie in the bone turn into osteocytes (bone tissue). This happens in balance with the natural breakdown of bone tissue (resorption) until our bones reach peak mass, usually between the ages of 20 and 30, depending on their location in the body. Then the balance shifts and there is more breakdown than growth.

By the time we are entering menopause there may already be osteopenia (low bone mass, which is considered a precursor to osteoporosis), and the risks will continue to rise. Many people think of osteoporosis as a disease of the elderly, but it is quite common for women in their early 50s to have osteopenia or even osteoporosis, and some are diagnosed in their 20s and 30s. Approximately 50% of people in the USA have osteopenia (Harvard Health, 2021), and women are twice as likely to have osteopenia as men, and four times likelier to have osteoporosis (Rinonapoli et al, 2021).

Given that many women will not have a bone density scan (DEXA) until they suffer a fracture, the proportion of women with osteoporosis may be higher than statistics show. It is sometimes called the “silent disease” because a person may not be aware that they have osteoporosis until they have experienced either a low-impact fracture or a vertebral compression fracture (VCF). This may be why we think it doesn’t occur until old age, when balance issues begin to cause more falls and posture changes because of VCFs can cause more chronic rounding of the spine.

Certainly there are more women in your classes than you know, and more than know themselves, who have low BMD, not least because in the five to seven years directly after menopause in particular, there appears to be an accelerated loss of bone mineral density (BMD).

Fractures related to low bone density are thought to be more common in people with osteoporosis than osteopenia. But interestingly, one study showed that people with osteopenia and low body weight had a greater fracture risk than those with osteoporosis (Tomasevic-Todorovic et al, 2018). This points to the need for adjustments to be made for people who have osteopenia, rather than waiting until it develops into osteoporosis. This could be half your female students over 50.

The starkest fact is that fractures after the age of 65 are associated with higher risks of mortality (Negrete-Corona et al, 2014). This is more the case for people in their 80s and 90s and you may not have many in your classes in that age group, but nonetheless it is significant and important.

It’s important to remember that bones are not just structural; they are the storehouse of minerals that affect our entire system, from muscles to neurological impulses. There is also a hormone-like secretion from the bones, osteocalcin, which has been linked to improved insulin function and memory, among other things. So looking after bones is beneficial not just for the bones themselves.

Sarcopenia (muscle loss) is a condition seen most obviously in later life, but reduction in muscle mass starts earlier. Keeping an eye on muscle mass and strength is therefore essential too. All our work for bones is intertwined with supporting our muscles; the two go hand in hand. Any contraction of muscle will stimulate the periosteum (fascia around the bone), which in turn stimulates the genesis of bone tissue.

It is my conviction that if we are working with women we are doing them a disservice if we don’t focus some of our offerings on bone strength and health, and protecting them from injury due to inappropriate asana, forceful adjustments, or falls. Care of osteoporosis and osteopenia in yoga classes should not be thought of as a niche area.

Can yoga help?

There is not enough rigorous and repeated evidence to definitively support the use of yoga to prevent or reverse osteoporosis. In my Yoga for Bone Health trainings I discuss why some research that may have lead you to believe otherwise is not robust, and what other avenues we can prioritize to support bones. However, a meta-analysis into the effects of Pilates and yoga on bone density found that these interventions resulted not in increased bone mass, but in a maintenance of bone in postmenopausal women. At a time when we would expect to see bone loss, this is encouraging. Note: better results were evident from Pilates than from yoga (Fernández-Rodríguez et al, 2021).

For the moment, the most robust research would lead us to be confident in saying that improving bone mass in postmenopause seems to be most reliably achieved by lifting heavy weight, multiple times per week, at an intensity of 80-85% of full effort (Watson et al, 2017). These are weights considerably greater than any you would be qualified or wise to include in your teaching and so would be better left to the gym.

In the general population, we also know that jumping, hopping, skipping, running, and dancing are beneficial (though advised against for people with fragility fractures). But remember, the effect of muscular action on bone growth is site-specific. This means that running and jumping will only positively affect the bones up as far as the lower one or two vertebrae, but not the rest of the spine—or the wrists, for instance.

How yoga can help

What I’ve just written may make you wonder what value you can possibly have for your clients with BMD loss. Wonder not! You have an excellent resource for this cohort. Bone health is not just about density, and yoga can help us to:

- develop all-over body conditioning that may make lifting weights and other forms of exercise safer (with “good form”)

- increase muscular strength to aid stability and decrease fracture risk

- avoid falls through its balance challenges and proprioception stimulus

- feel more confident moving our body.

And you, as teachers, can help women after a diagnosis of osteopenia to feel confident as you expertly help them re-find movement at a time when they may feel unsure about what is safe anymore.

As a long-term yoga practitioner with osteoporosis, I know yoga doesn’t guarantee everything. I also know the dismay as I stepped back on the mat wondering if yoga still had a safe place in my life. When I posted about vertebral compression fractures in yoga students, one reaction which lit a fire in me to figure this out for myself and my students was “these people would be better off not at yoga but going weight-lifting”. Now, that’s a valid statement. Weights are indeed the most reliably effective way to build bone, and some asana are unsafe for those with low BMD. But I thought to myself: How would it feel as a lover of yoga to be told by your teacher, “My classes are no longer relevant for you”? I believe if we learn enough we can keep our classes relevant and safe for all.

Protection first

Yoga can injure, of course. It can be tricky to know whether some injuries are a result of yoga, especially in the case of VCFs which can occur slowly over time. Though limited in that regard, one study found that “increased torsional and compressive mechanical loading pressures occurring during yoga SFE [spinal flexion exercises] resulted in de novo VCF [vertebral compression fractures]” (Sfeir et al, 2018). This was not a huge study, but I would not be happy to be the teacher that led even one person to a vertebral compression fracture or any other fracture.

The study concluded that “the appropriate selection of patients likely to benefit from yoga must be a cornerstone of fracture prevention.” I would say that, rather than “selecting” patients (i.e., only those not at risk) and excluding those with osteopenia and osteoporosis, we should aim to make yoga safer for all.

- Teach balance and strength to maintain good posture and to avoid falls.

- Keep any students with osteopenia or osteoporosis whom you feel are at risk of falling near a wall during balance postures. (Sometimes, so as not to expose people who don’t want to consider their vulnerability, I bring the whole class to the wall and then say they can use it or not as they see fit.)

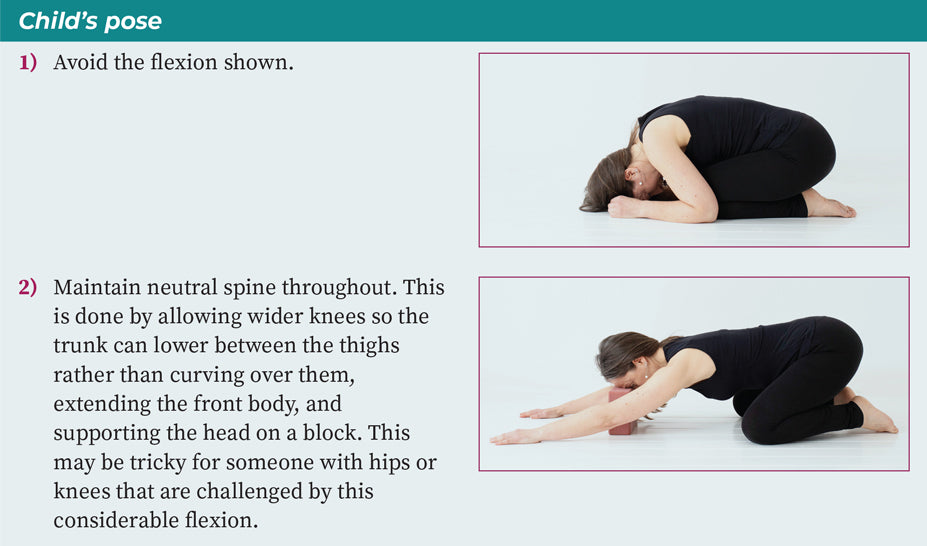

- Avoid deep forward folds except with neutral spine. Never suggest pulling on toes to go further, and avoid levering or pushing into flexion.

- Offer back-strengthening exercises, because strong back muscles can reduce the risk of VCFs (Sinaki et al, 2002).

- Be cautious with hands-on adjustments and avoid pulling or pushing your student into any pose.

- Avoid end-of-range or twists of the spine, especially if there is a flexion included (whether intentional or unintentional).

- Avoid the student using the arms to lever into twists (especially avoid bound twists).

Adjusting some common postures for safety

When you approach postures or practices that have risks for osteoporosis, please consider including your students via variations rather than simply saying, “Don’t do this if you have osteoporosis.” For instance:

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW