Well-Being Across the Decades

This is an excerpt from Fitness and Well-Being for Life 2nd Edition With HKPropel Access by Carol K Armbruster,Ellen M Evans,Catherine M Laughlin.

In the first few chapters, we discussed the importance of a positive outlook on well-being. We promised to minimize scare tactics, avoid prescriptive recommendations (e.g., you must do this or that!), and discourage quick fixes. Rather, we wanted to provide general guidelines for healthy moving, eating, and sleeping choices, and provide ideas so that you can make healthier choices. Finally, we wanted you to build your behavioral toolkit and motivational muscles. We hope we have broadened your outlook on the importance of integrating movement and well-being practices into your life—not just during your college years but for a lifetime.

We hope this culminating overview of fitness and wellness concepts will help you remember that life is precious, and that how you choose to live it will dictate your life span and, as importantly, your health span. Investing in these behaviors that enhance your well-being will give you energy and vitality to not only do what you have to do but also what you want to do every day. And because we are social animals, it is imperative to surround yourself with people who also invest in healthy behaviors to maximize their well-being. This choice will ultimately make your own decisions to move more and sit less much easier. You will know when you have arrived at “living well” because you will not have to think about it—you will be too busy living it.

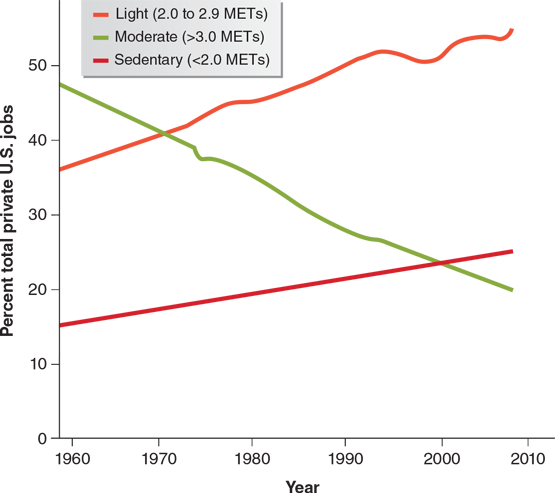

Putting positive well-being practices at the forefront of our daily lives can and will make a difference in your quality of living now and in your future decades. However, you will need to be very intentional about your well-being practices because our modern world makes the less healthy choice the easy choice at every turn. For example, as shown in figure 15.1, the U.S. workplace has become increasingly sedentary over the decades, and the trends continue—note the increase in sedentary and light work compared to the reduction in moderate work from 1960 to 2010 (Church et al. 2011). This means we are sitting more and moving less at work because our jobs require less daily physical activity. As discussed in previous chapters, the World Health Organization’s guidelines on physical activity and sedentary living (Bull et al. 2020) recommend reducing sedentary behavior and increasing physical activity for better health—remember, some physical activity is better than none.

Reprinted by permission from T.S. Church et al., “Trends over 5 Decades in U.S. Occupation-Related Physical Activity and Their Associations with Obesity,” PLOS ONE 6, no. 5 (2011): e19657. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License.

The majority of the research introduced in this book tells us that in order to be well, we need to move more, sit less, and sleep better. The integrated ebb and flow of the wellness continuum (chapter 1) reminds us that our relative efforts (i.e., how much and what we do) to improve the various areas of wellness differ across the life span. Concepts introduced in chapter 2 remind us that all movement counts, and some days you will engage in intentional exercise, whereas other days you will have lots of physical activity. Ideally, most days you will have both types of movement. Reducing your sedentary behavior and your sitting time should also be a goal every single day. Remember the equation: human movement = exercise + physical activity – sedentary behavior. In addition, the importance of your movement pattern over a 24-hour period (an average day) is gaining more importance. The 24-hour activity cycle paradigm reminds us that time spent in sleep, sedentary behavior, light-intensity physical activity, and moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity interact and impact multiple domains of health in complicated and unknown ways.

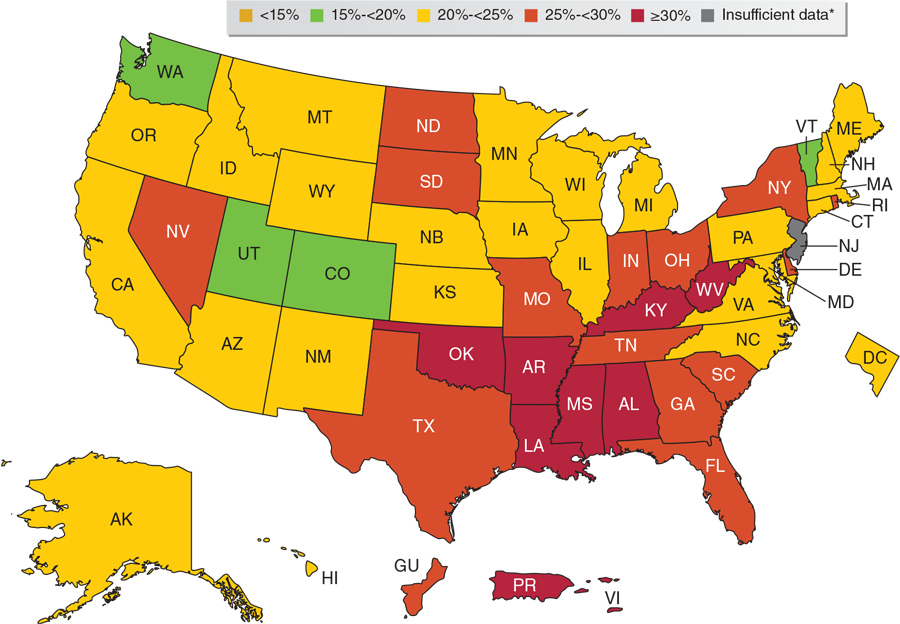

However, adult physical inactivity rates are at an all-time high as a result of the continued decline in daily movement practices. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022), the highest prevalence of inactivity in the United States is in Puerto Rico (49.4 percent), compared to the lowest in Colorado (17.7 percent). Regionally, states in the South have the highest prevalence of physical inactivity (27.5 percent), followed by the Midwest (24.7 percent) and West (21.0 percent). On average, a quarter of the people living in the United States are physically inactive (see figure 15.2).

Reprinted from "Adult Physical Inactivity Prevalence Maps," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last modified February 17, 2022, www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/inactivity-prevalence-maps/index.html#overall.

Living Longer or Living Better?

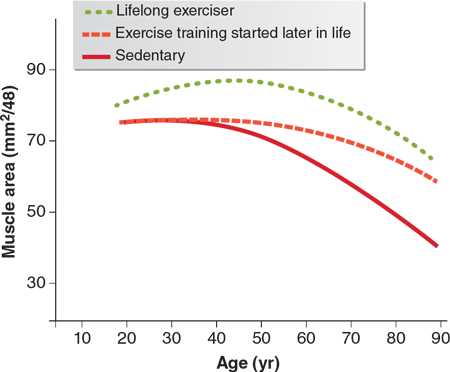

The World Health Organization (2022) reports that by 2050, the world’s population of people aged 60 and older will double to 2.1 billion, and the number of persons aged 80 and older is expected to triple to reach 426 million. By 2030 (just around the corner), 1 in 6 people in the world will be aged 60 years or over. The choices you make now will likely influence if you make it to 80 years of age and how well you live in these older years. A landmark study following Harvard alumni from ages 35 to 74 taught us that moving throughout the life span might add more years to your life (Paffenbarger et al. 1986). Although all your body systems decline with advancing age, starting a physical activity program early and keeping it up throughout your life will help “bend the aging curve” for key systems, helping you retain your functional fitness with age. For example, being a consistent mover will help delay muscle decline as you age, which will keep you active and independent in your older years (see figure 15.3). There is much research supporting the importance of intentional exercise (especially resistance training), regular physical activity, and minimal sedentary behavior to preserve function for the heart, brain, and metabolic and immune systems, to name a few. This protection becomes obvious in midlife and beyond.

Reprinted by permission from J.F. Signorile, Bending the Aging Curve: The Complete Exercise Guide for Older Adults (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2011), 13.

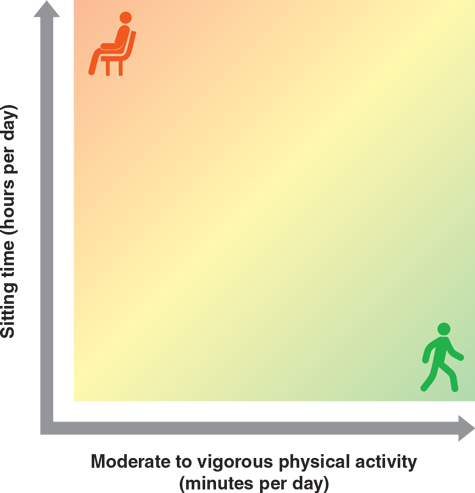

Another example of this current data is the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Scientific Report (Katzmarzyk et al. 2019) that described a strong link between sedentary behavior (mostly sitting time) and increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). As these two diseases influence other chronic diseases and conditions (e.g., cancer), and with CVD being our top cause of mortality, it is not surprising that sedentary behavior is also linked to mortality. As an example, figure 15.4 shows the association between sitting time and moderate to vigorous physical activity with risk of all-cause mortality. Beyond life span and health span, most middle-age and older adults value living independently in their own homes, having autonomy, and making decisions about how and where they spend their time. Your well-being will directly influence your ability to go and do in your later stages of life. Invest in your future self now.

Adapted from 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report.

It is up to you to move more so that you can overcome the trend of sedentary living and live a longer, more independent life.More Excerpts From Fitness and Well-Being for Life 2nd Edition With HKPropel Access

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW