Understanding post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

This is an excerpt from Psychological Benefits of Exercise and Physical Activity, The by Jennifer L Etnier.

Bob was a Vietnam War veteran who was working as a musician and lived in a small home with his wife and two sons. Bob had recently injured himself, and the explanation of what happened was unique. He had been having trouble with nightmares from his military experiences in Vietnam, and they were affecting his ability to get a good night’s sleep. He was upset about the vividness of the dreams, which were forcing him to relive both real and imagined situations in Vietnam. But he was also concerned for practical reasons because his thrashing about and vocalizations were keeping his wife up, making it challenging for her to be fully rested for her 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. shift as a nurse. One evening when his sons were away at a friend’s house for a sleepover, Bob decided to sleep in the bottom bunk in his boys’ bedroom. He thought the change in location for sleeping might help with his nightmares and also give his wife a chance to get a good night’s sleep. In the middle of the night, Bob had another nightmare that involved him being trapped in a cage. In an effort to escape his dream prison, he began thrashing around. As the nightmare escalated, Bob kicked his legs out straight, knocking the footboard of the bed out. He was startled to wake up in excruciating pain when the footboard of the top bunk crashed down on his shins. Clearly, Bob was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and panic attacks, and this was his wake-up call to seek help. Following this episode, Bob contacted the Veterans Affairs agency and began treatment with a psychiatrist. The psychiatrist enrolled Bob in a therapy group program to focus on identifying triggers, reducing and managing stress and anxiety, and building self-esteem. The psychiatrist also prescribed drugs to treat his depression and anxiety.

The opening scenario focuses on a person who is experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is linked to panic attacks and anxiety. Although therapy and pharmacological interventions can be successful in treating anxiety, it is important to appreciate the potential role of exercise as well. In other words, in addition to the treatments prescribed, the question is if the psychologist should also recommend exercise. This might be particularly relevant in this example because upon retiring from the military, Bob experienced a transition toward being less physically active. We will consider how single sessions of exercise and chronic exercise can affect the experience of anxiety.

What Is Anxiety?

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines anxiety as “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes like increased blood pressure” (American Psychological Association, 2022). We have all experienced anxiety in an acute sense, and this is referred to as state anxiety. Examples might be when you have a big exam that you do not feel prepared for, when you are asked to give a public presentation, or when you have an important sport competition. In these situations you are likely to experience a variety of symptoms including sweaty palms, nausea, a racing heart, and tunnel vision. The experience of feelings of anxiety in the face of these types of evaluative situations is common and natural, and the symptoms typically abate relatively quickly either during or following the event. These episodes of state anxiety are experienced by everyone and can be managed with various coping techniques including deep breathing, controlling negative thoughts relative to the situation, and even imagining yourself being successful.

Although the experience of state anxiety is normal and ubiquitous, the experience of chronic anxiety is less common. When anxiety is experienced over an extended period of time, it is considered trait anxiety. When trait anxiety is particularly long-lasting (6 months is often the criterion), is irrational or disproportionate to the threat, and affects daily living, it is considered to be a clinical form of anxiety or an anxiety disorder. Within any given year, approximately 19% of Americans are affected by various forms of anxiety disorders in ways that have a significant impact on their daily functioning.

American Psychological Association

The American Psychological Association (APA) is an important scientific and professional organization that has more than 100,000 members and affiliates including researchers, practitioners, and students. The organization hosts an annual meeting at which research papers are presented. It advocates to promote the unique benefits of psychology in terms of both the science of behavior and the benefits to individuals in their daily lives. In particular, APA is engaged in advocacy on a variety of topics including health disparities, federal funding for psychological research, civil rights, criminal justice, gun violence, suicide, and substance use disorders. Within the APA is a division called Division 47: Society for Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, which is an interest group that focuses on topics related to exercise psychology.

What Are Anxiety Disorders?

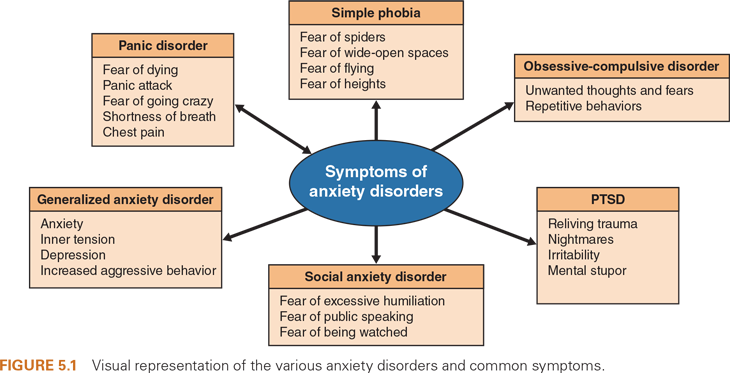

The APA identifies several major types of anxiety disorders including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and PTSD. Although these disorders have anxiety in common, they differ in terms of the specific nature of the experience (figure 5.1).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder is defined by the experience of recurring fears or worries that often have unclear specific causes and that affect a person’s ability to perform daily tasks. The target of the fear or worry might seem rational, such as being worried about finances or performing well at work, but the anxiety is considered a disorder when the fears or worries are persistent or out of proportion to the actual potential consequences of an event. For example, if a 36-year-old man is living paycheck to paycheck and is losing sleep and experiencing anxiety related to his finances, this is a reasonable response. But if a 36-year-old man who has stable employment, makes a good salary, and has a reasonable amount of money in a savings account is losing sleep and experiencing anxiety related to his finances, this is probably disproportionate to the actual threat. Generalized anxiety disorder can manifest as paralysis through analysis, where people are unable to function because they are considering every possible negative outcome relative to a decision they might need to make. These worries often result in difficulties handling uncertainty, indecisiveness, and sensing threat in a wide range of situations. To meet the definition of generalized anxiety disorder provided by the APA, this sense of anxiety has to be experienced on most days for at least 6 months.

Panic Disorder

Panic disorder is characterized by the experience of sudden, intense feelings of terror that have no obvious or justifiable cause. These perceptions are accompanied by physiological responses or symptoms that include shortness of breath, heart racing, sweating, and feeling dizzy or faint. They typically reach maximum intensity after about 10 to 15 minutes. Although many people might experience an occasional panic attack, this would be diagnosed as a mental health disorder according to the APA if the panic attacks were recurring on a regular or semi-regular basis and were accompanied by concern about future attacks and evidence of maladaptive changes in behavior related to the panic attacks. In some cases, individuals are able to identify the triggers for their panic attacks and might self-select to avoid those triggers as a way to minimize the likelihood of an attack. Common triggers include caffeine, a traumatic situation, a reaction to medication, and life stressors. In other cases, there are no identifiable triggers, and the panic attacks occur seemingly at random. Panic attacks sometimes can occur during sleep as in the example of Bob provided at the start of this chapter.

Phobias

Phobias are another type of anxiety disorder, and they are experienced by about 19 million Americans. A phobia is an unrealistic and debilitating fear of something specific. Phobias can be experienced relative to almost any stimulus, but common phobias include fears of spiders (arachnophobia), snakes (ophidiophobia), dogs (cynophobia), heights (acrophobia), wide-open spaces (kenophobia), and small spaces (claustrophobia). One distinction between panic disorder and a phobia is that with a phobia, the cause is always identifiable but doesn’t warrant the extreme feelings of fear that are experienced. For example, consider Rene, who has a phobia about mice. This phobia controls many decisions she makes; she will not consider staying at a state park cabin because she once saw a mouse at a state park when she was a teenager. One day Rene saw a mouse in her home and immediately panicked. She jumped up on a sofa and started hyperventilating while simultaneously screaming uncontrollably. She picked up a pillow to beat off her perceived attacker. Luckily, her son came to her rescue and was able to escort her out of their home. But she was unable to return to her home until the pest-control people were called, had treated the home, and had repeatedly assured her that they had taken care of all mice. Even with these reassurances, she was on high alert for weeks in fear of seeing another mouse in her house.

Do you have any phobias? What are they? How long have you had them? How do you react when faced with the trigger of your phobia? Have you done anything to reduce your phobia? If you don’t have a phobia, imagine how you feel when you are watching a really scary movie—perhaps on the edge of your seat, nervous, jumpy, and ready to flee. Imagine experiencing these feelings in an ongoing fashion or in response to situations you encounter frequently in your life. This gives you an idea of the experiences of individuals with clinical anxiety disorders.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is evident when a person has thoughts or feelings (obsessions) that are persistent, unwanted, and uncontrollable. To reduce the anxiety caused by these obsessions, the person participates in repeated behaviors such as hand washing that become compulsive. The person’s behaviors then come to reflect perfectionism, excessive orderliness, and a need for control of situations and relations with others. Although we all might have habits that we repeat such as biting our nails or double- and triple-checking our alarm clock the night before an important event, these are not compulsions unless we spend at least an hour per day doing these things, they feel uncontrollable and unenjoyable, and they interfere with our normal activities. OCD has a stronger familial link than other anxiety disorders, meaning that children of parents with OCD are themselves more likely to have OCD.

obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)—OCD is when a person has thoughts or feelings (obsessions) that are persistent, unwanted, and uncontrollable, and to reduce the anxiety caused by these obsessions, the person participates in repeated behaviors such as hand washing that become compulsive.

PTSD

PTSD is experienced when a person has previously been exposed to a traumatic event and then relives that trauma when exposed to reminders of the event. PTSD is common in military veterans and in people who have lived through natural disasters or who have witnessed horrific events such as a deadly car accident or a shooting. It is estimated that 3.5% of Americans have PTSD, and 7.6% of veterans experience PTSD (Hegberg et al., 2019). The symptoms of PTSD include reliving of the traumatic episode, negative thoughts and feelings, avoidance of reminders (triggers) of the event, and heightened arousal. PTSD is characterized by intense feelings of sadness, fear, or anger and might be typified by excessive reactions to ordinary events that serve as triggers. For example, the sound of a car backfiring or seeing a news story about a shooting might serve as a trigger for anxiety, depression, and panic in a person with PTSD. Although PTSD resolves on its own in approximately 50% of individuals, it can last for years in other people. Individuals with PTSD have higher chronic health issues including diabetes and obesity and show reductions in their physical activity participation as compared to their behavior prior to the experience of PTSD.

Separation Anxiety Disorder

In addition to the anxiety disorders listed here, you might be familiar with one other anxiety disorder. Separation anxiety disorder typically becomes evident during childhood and, therefore, is considered by APA to fall under a separate section of disorders specific to diagnoses that take place in infancy, childhood, or adolescence. You might have seen this in a toddler left at school for the first time. The child might cry and cling to her parents when they attempt to leave the child at school. To be considered a disorder, it would be characterized by excessive distress relative to a child’s developmental age and in response to anticipated or actual separation from loved ones. If the distress is intense or prolonged and interferes with normal activities, this might meet the criteria for a clinical disorder.

Reflective of the fact that so many different types of anxiety disorders exist, empirical evidence is limited specific to the effects of exercise for many of these forms of anxiety. Instead, the vast amount of research is focused either on anxiety as a state-level emotional response or on generalized anxiety disorder. The body of evidence on PTSD and panic attacks is growing, but research on exercise and OCD or phobias is extremely limited.

Do you know anyone who has been diagnosed with one of these clinical disorders? If so, you likely have a sense of how life-altering these disorders can be as the person tries to navigate their lives. Individuals with anxiety disorders are known to report lower quality of life, to have challenges in their personal relationships, and to have difficulty meeting demands of their employment. If you know someone with a clinical disorder, do you know if they have ever tried exercise as a way to mitigate their anxious reactions? We’ll learn more in this chapter about the potential role of exercise in treating anxiety disorders.

More Excerpts From Psychological Benefits of Exercise and Physical Activity, TheSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW