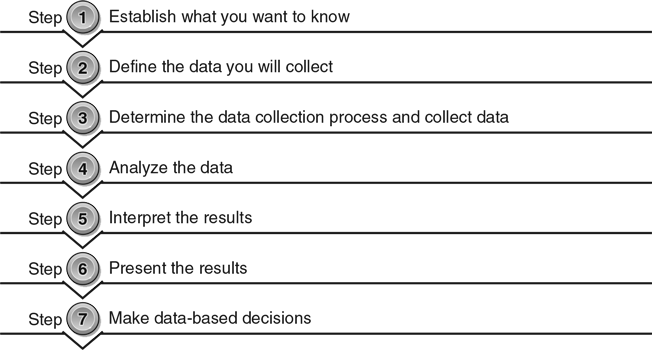

Steps in the sport performance analytics (SPA) process

This is an excerpt from Sport Performance Analytic Methods With HKPropel Access by John R Todorovich.

A standardized and systematic approach to the SPA process establishes consistency in the procedures employed. The standardized sport performance analytics model (SPA model) (figure 1.1) is a seven-step process that, when followed, provides sport analysts with a consistent, focused, and ordered series of steps that ensures consistency in the sport analytics process. This is much akin to the scientific method that researchers and scientists use to conduct experiments and solve difficult problems; however, the SPA model includes steps designed specifically for sport professionals conducting sport performance analysis.

The SPA process begins with a question: What do you want to know? Once that question is effectively answered, the sport analyst then progresses through the other steps in the SPA model until informed and objective decisions can be made by coaches or other stakeholders in the team’s success.

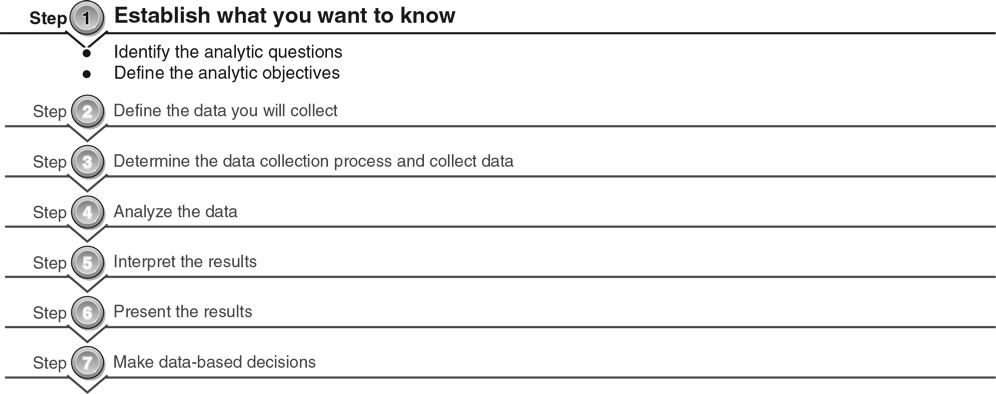

Step 1: Establish What You Want to Know

Before any data collection or analysis can begin, the sport performance analyst must first decide what exactly the coach, individual, or team wants or needs to know (figure 1.2). One coach may be interested in analyzing their players’ health before and during a competition to determine how to best utilize players during a game. Another coach may want to collect data on an opponent’s strengths and weaknesses during game play to make decisions about planning for an upcoming competition. The analyst can respond to any of these needs in a variety of ways.

The purpose of step 1 is to define the analytic questions that will guide the remainder of the process. Analytic questions that are clear and precise will produce better results. Following are examples of effective analytic questions a sport performance analyst may use.

- What is the shooting percentage of each player on a basketball team?

- How often do soccer players pass a ball with their dominant foot and non-dominant foot during a match?

- What is the reaction time of a defensive football lineman in response to the movement of the football to begin the play?

- Does the opponent usually throw or run a football on second down, and does this change from the first to the second half of the game?

Although this may seem like a simple step in the process, it is often one of the hardest. Coaches and other decision makers often think they know what type of information they need to help them, but in reality, they may need very different information. For example, a coach may be interested in the players’ endurance because they seem to slow down and fail to perform as well at the end of the game. In this scenario, the coach may ask for the average mile run time for each player and note after how many plays or minutes of the game each player’s performance decreases. Both measures may help determine the endurance level of an athlete, but the first is a measure of how fast the player can run a mile, while the second provides important data for game stamina and can help determine when best to use the player in the game.

When beginning the SPA process, the analyst first evaluates the general questions posed by the decision makers. Sometimes the questions are clear and the expected outcomes are very easy to ascertain. Unfortunately, there are many other instances where the questions asked are too vague, complex, or irrelevant for the analyst to take immediate action. The analyst must review each question carefully with the intention of refining it to a degree where very explicit outcomes can be articulated. This can be challenging because each question may produce one or more desired outcomes, with each requiring different actions. Under the best circumstances, the same data can be analyzed and used to address multiple outcomes. However, if the degree of data to be collected and the complexity of the data collection process become very cumbersome, the analyst may need to work with decision makers to make the questions more manageable.

As a standard practice, questions that generate more than three outcomes are recommended to be refined before analysis begins. For example, a coach may ask how to increase the number of shots taken by players on their lacrosse team. If the question is not refined, then the analyst may collect a wide range of data such as the distance from the target that shots are taken, the angle of the shots, which player is taking the shots, and many more. The analyst may want something more manageable, such as “How do we increase the percentage of shots that are on frame (i.e., would score if not blocked by an opponent) and taken within 10 yards of the goal?” This example illustrates how the question could be refined to produce a more precise outcome for the decision makers. The analyst can work with decision makers at this stage to help them focus on their goals and questions. Properly done, this can prevent weaknesses as the SPA process continues.

The challenge, then, for the sport performance analyst is to help coaches and other decision makers refine their interests in order to better provide more meaningful information to them. If this step in the process is not done properly, the remaining steps will be completely ineffective. To resolve this issue, the analyst next determines the specific objectives of the questions. Analytic objectives within the SPA process are carefully worded statements that clearly describe all the data that must be collected and analyzed to provide desired information for appropriate decision makers. These statements cannot be vague, and they must include measurable components. These analytic objectives will help the analyst determine the variables that will be analyzed in step 2 of the process.

SPA objectives should be written as carefully and clearly as possible and should be robust enough to completely address the desired outcomes of the analysis. At this stage, the analyst determines whether the analysis will involve a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Next, the analyst must determine the number of objectives that will be analyzed per each question or outcome. If more than three objectives are found to be necessary, the analysist should revisit the question and desired outcomes posed by the decision makers. Analysis beyond three objectives becomes complex, cumbersome, often very costly, and sometimes at least partially irrelevant, and data are inefficient to acquire and analyze. For example, wanting to know which players on a team have a higher scoring percentage is precise and measurable, whereas asking the analyst to determine the best or most valuable player on the team would be very difficult to do with that question alone. These analytic questions are important in particular because they often set the foundation for hypotheses and statistical procedures that will be completed to conduct the analysis (see chapter 5).

Making a decision about the desired outcomes rather than just asking what type of information is required reframes the focus of this step in the SPA model. As an example, asking how to win the league championship (i.e., informational) is not as useful as collecting data and analyzing variables and factors that might improve scoring percentage (i.e., outcomes). This helps the analyst refine the analytic approach in conjunction with coaches and other decision makers. Once objectives are clearly identified, the analyst is prepared to move to step 2 of the SPA model.

Step 2: Define the Data You Will Collect

Many types of data can be collected to answer the questions identified in step 1. If the analyst was successful in identifying the objectives of the decision makers, the next step is to carefully plan exactly what type of data will have the greatest impact for the decision makers. Specifically, the analyst must determine both the category and depth of the data. Data categories include the broad areas of quantitative or qualitative data. In later chapters, these data categories are described as having more precise classifications such as performance, process, and biometric data. Although both categories are discussed in detail throughout the book, at this point, it is important to understand that quantitative data usually consist of numbers (e.g., frequency of events), while qualitative data usually consist of words and descriptions of events. Depth of data involves the amount of data that will be collected.

From a process perspective, the analysis will first review the objectives determined in step 1. The next part of step 2 involves consideration of the data categories and how much data are needed (i.e., depth) to provide the best information for the decision makers. In general, if the data are to be used for descriptive reports or to make predictions for large numbers of players, the analyst would likely choose the quantitative data category with a large sample population to provide a very deep level of analysis. If the data are to provide a detailed description of the biomechanical deficiencies in a baseball pitcher’s throwing mechanics, a detailed qualitative description including only one person would be the most acceptable choice.

During step 2, the analyst will expand on the analytic questions and refine exactly how the questions will be answered. To do this, the types of variables, the unit of analysis, and factors such as time consideration, validity, and reliability of data are considered. Each of these concepts is covered later in the book. After careful consideration of the type of data that will be collected, the analyst can then determine the data collection process and begin collecting data in step 3 of the SPA model.

Step 3: Determine the Data Collection Process and Collect Data

Step 3 in the SPA model involves two parts. First, the sport analysist decides what method will be used to collect data, and second, the analyst will collect data. Data collection is largely dependent on the analytic question that is asked, and factors such as the cost of collecting the data are important considerations in the data collection process. (See chapter 3.)

When an analyst is interested in learning what is happening during an event, as much descriptive material as possible is gathered. This is usually done in the form of taking notes, transcribing interviews, watching videos of an event multiple times, or looking through written documents such as practice or game plans. Each of these data pieces provides the analyst with information that can be explored more deeply. This is useful when one is interested in learning about something but does not have a strong guess as to what might be causing the phenomenon to occur. For example, if players do not seem to be making significant gains in their technical skills over time, the analyst may use qualitative methods to observe training and training plans as well as interview both players and coaches to see if the answer can be deduced from the qualitative data. Again, this approach to data analysis is covered in detail later.

Step 4: Analyze the Data

Once the data are collected, the analyst is ready to begin making sense of the information by analyzing it. This involves some very detailed procedures, and they are covered throughout this text (see chapters 4 through 7), but it is important to have a general understanding of the process to understand step 4 of the SPA model. As previously discussed, the objectives of the analysis and the types of data collected will dictate the analytic procedures that will be employed to better understand the collected data. This includes either quantitative or qualitative analyses.

Quantitative data analysis within the SPA process falls into three categories: descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, and predictive statistics. First, descriptive statistics describe the data by collecting, sorting, organizing, and completing calculations that produce descriptive measures. The primary purpose of descriptive statistics is to make sense of the data and inform people what the information tells us. A second type of analysis is inferential statistics, and it uses data collected on a sample of people to explore whether groups differ in any way.

A third quantitative analysis is predictive statistics, which uses current or known data to make predictions about future performances. While chance cannot be completely removed from the analysis, some predictions are stronger than others simply based on the strength of the variables. For example, the likelihood that someone will be able to jump and touch a standard basketball rim is increased as one gains height and arm length. Although not an absolute measure, these types of analysis are of particular interest to coaches and other decision makers in the sport industry. Predictive statistics are used by analysts to conduct predictive analytics.

Qualitative data are analyzed through careful and consistent observations of events, by either looking for consistent themes in the data or by comparing the data against a preplanned set of criteria. Qualitative analysis can produce findings that emerge from the data itself or can be the result of analyzing specifically prescribed material.

Step 5: Interpret the Results

After the data have been collected and analyzed, the analyst must then interpret the results. For quantitative analysis, this usually involves statistical procedures that produce test statistics and results tables.

Each statistical procedure is a tool that answers a specific question based on the data (see chapters 4 through 6). There are statistical procedures for determining whether there are differences between two or more groups, for determining the impact of particular variables on group differences, and for making predictions about future performance based on past performance. These statistical tools are only as effective as the data collected, the statistical procedure used, and how the results are intended to be used by decision makers. While these statistical tasks can be automated through software programs, it is important that sport performance analysts understand the conceptual basis and limitations of each statistical procedure and how they can be used to learn about their numerical data collection.

Qualitative data interpretation in many ways calls for creativity and robust understanding of the data (see chapter 7). This is because the analyst essentially becomes the instrument for interpreting the results of the data. When the data are robust and include open-ended questions, the analyst has particular obligations not only to carefully interpret the data but also to decrease personal bias and be willing to justify the trustworthiness of the data. If the qualitative data are examined using very specific questions or qualitative guidelines, the process becomes more objective, more refined, and less sensitive to unexpected outcomes. For example, a rubric with specific qualitative criteria can be used to make qualitative decisions about the data, such as the mechanics of an overhand throw or the execution of a specific game plan during a competition.

By this step in the process, the analyst will have determined specific objectives, determined the type of data to collect, collected the data, analyzed the data, and interpreted the results. In the next step, the decision makers begin to consider the data.

Step 6: Present the Results

In step 6 of the SPA model, the analyst prepares and presents the data to decision makers. This can be difficult because coaches, players, and other stakeholders are often not interested in the specific details of the data. The decision makers want clear, concise, and pertinent information that is both valid and reliable to help them achieve success as they define it.

Data presentation can take many forms (see chapter 8). Styles can include figures, graphs, tables, narrative reports, and presentations. These can be presented digitally, verbally, on paper, and even orally. The key is to present the data in a way that is easy to understand by everyone who needs it.

There are many methods for presenting data. However, most people benefit from being presented first with relevant data in the simplest and most concise manner. This is often called a data dashboard and is similar to the car dashboard, which shows various instruments that provide useful data for the driver in a quick and efficient way. These data dashboards are often a collection of data visualizations that are valuable for decision makers either during a competition or later when evaluating the outcomes of a competition (figure 1.3). Similarly, data dashboards can be created for sport decision makers.

It is also recommended that the analyst provide a second layer of data presentation that supplements and supports the data dashboard. This second layer would include additional or more refined data. For example, the dashboard might provide a football coach with the current down and distance, while the second layer of data would provide more information such as the average down and distance during the game or location on the field. This is useful for supporting anomalies or unusual findings within the data dashboard itself.

Step 7: Make Data-Based Decisions

Step 7 is where decision makers use the data to make decisions. If each step of the SPA process has been carefully followed, the decision makers will be able to draw a clear connection between the analysis objectives and the results they are presented with (see chapter 9). A large benefit of SPA is the capacity of the data to help decision makers overcome their biases. For example, in Moneyball, coaches and administrators used data to overcome their biases about the value of players. In practice, analysts rarely play a decision-making role at this stage in the process beyond providing further explanation of the data or supporting the validity and reliability of the results.

As an example of data-based decision making, consider a soccer coach who wants to analyze situations where there is a one-versus-one challenge between a player and the goalie during team play. The intention is to increase the likelihood of scoring a goal. After clarifying the analytic question (SPA model step 1), the analyst and coach agree that analysis of defensive movement in relation to where the offense attacks is warranted. Through the analytic process, it is revealed that the opponent’s goalie and defenders always shift to the right when the attack is in the middle. The coach can then use that information to create an attacking plan where the offense attacks the middle, draws the defenders to the ball and to the right of the goal, and then passes to a left wing who is attacking the box in the open space.

More Excerpts From Sport Performance Analytic Methods With HKPropel AccessSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?