Selecting activities to improve current functioning, develop skills, and utilize strengths

This is an excerpt from Therapeutic Recreation Leadership and Programming by Robin Kunstler,Frances Stavola Daly.

Activity Analysis

To determine which activities are the most suitable for a client or group of clients in a particular setting, the TRS conducts an activity analysis. Activity analysis is a systematic procedure for identifying the specific behaviors needed to participate in a given activity. These behaviors can be categorized according to the four behavioral domains: physical, cognitive, affective or emotional, and social. Within each of these domains are specific skills and behaviors that are used in doing the activity. For example, playing a game of cards requires

- cognitive skills—knowing the rules and strategy of the game;

- physical skills—fine motor manipulation of the cards and visual acuity;

- social skills—taking turns and engaging in conversation with other players; and

- emotional skills—feeling positive, enjoying the experience, and coping with competition and winning and losing (Mobily & Ostiguy, 2004).

It is critical to analyze the activity as it is typically played or engaged in, and not for any particular disability or condition (Stumbo & Peterson, 2009). Once the TRS understands the skills needed to do the activity, she can select the activity for a particular client to help improve his current functioning, develop new skills, and utilize his strengths. A card game can be selected for a client whose goals include improving fine motor skills, cognitive functioning, or social interaction. Also, the client may have enjoyed playing cards in the past, and being able to play again may have significant meaning to him and contribute to his quality of life. The activity analysis has revealed that card games can help meet these goals. At this point the TRS can determine the adaptations necessary to enable the client to participate in the activity. A client who does not have the fine motor skills to hold the cards can use a piece of adapted equipment, such as a card holder, to enable participation. A client who has difficulty processing information quickly can be given more time to take his turn. Activity analysis serves as a means to understand both what skills are needed in order to do the activity and which skills can be developed or enhanced by participation in the activity. Through the process of analyzing an activity, the TRS obtains essential information that leads to modifying or adapting activities to the functioning level of the particular client (Shank & Coyle, 2002).

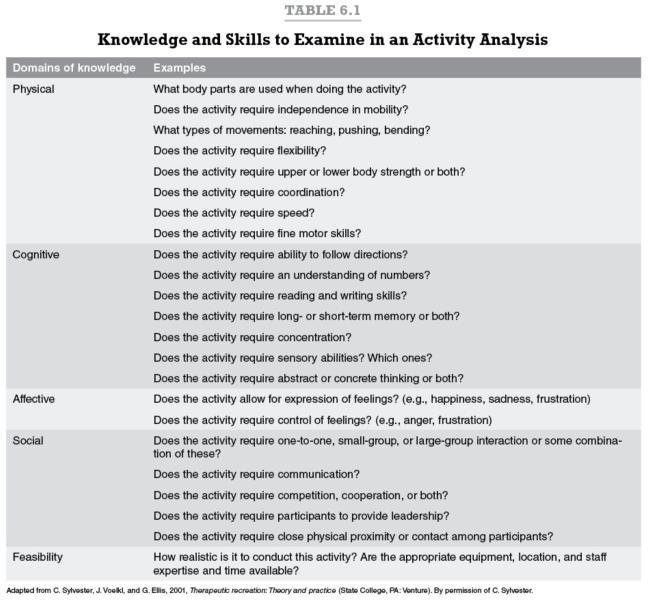

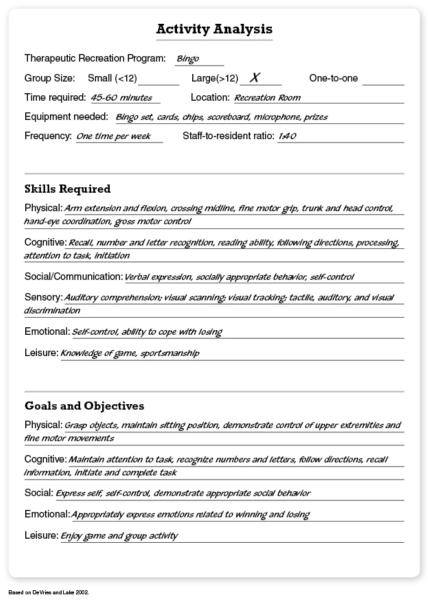

One of the most valuable aspects of activity analysis is that it provides the TRS with a rationale for selecting a particular activity. The rationale can be used to communicate the benefits of participating in a given activity to the clients, their families, and the other professionals. The TRS should have a thorough understanding of why she has selected an activity for the client and be able to articulate this rationale in a clear and comprehensible manner so others see its value. Even bingo can be played for its therapeutic value, as shown in the activity analysis presented by DeVries and Lake (2002). See figure 6.1 for their activity analysis of bingo and table 6.1 for a list of the knowledge and skills to examine when conducting an activity analysis (Sylvester et al., 2001).

Let's look at another game, checkers. Checkers requires vision and fine motor dexterity to grasp and move the playing pieces, cognitive skills for knowing the rules, use of strategy to make decisions about moves, and concentration. It also requires social skills of taking turns and sitting quietly while the opponent contemplates his moves and emotional control during the game and when responding to winning or losing (Stumbo & Peterson, 2009). Checkers might be a good choice for a client who is overcoming social isolation and is more comfortable interacting one to one. If needed, the pieces can be modified to be easier to grasp. When modifying activities, keep the activity as close to the original as possible. By making only the necessary modifications, the activity is more similar to the way it is typically engaged in. This is more fun for clients and also facilitates their transfer of skills to more typical environments. Modify only as necessary to enable the client's successful engagement. Individualize modifications to the needs of each participant. Modifications may be temporary, used only until the client develops the skills and knowledge necessary to participate as fully as possible. For example, as a client's ability to concentrate increases, he will no longer require extra time to take his turn. For a comprehensive discussion of activity analysis, see Therapeutic Recreation Program Design by Norma Stumbo and Carol Peterson (2009); any edition of this classic TR textbook is highly recommended.

This chapter presents the five broad categories of TR programs, with descriptions of specific activities, their benefits and applications to a variety of clients, and risk management concerns. Each TR program is supported by evidence from research findings and the literature demonstrating the efficacy and value of the activity in producing the desired outcomes and providing the client with a meaningful experience.

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW