Design and use of adapted macrocycles

This is an excerpt from Training and Conditioning for MMA by Stéfane Beloni Correa Dielle Dias,Everton Bittar Oliveira,André Geraldo Brauer Júnior,Pavel Vladimirovich Pashkin.

By André Geraldo Brauer Júnior, Jeffrey Williams, Brian Binkley, Stéfane Beloni Correa Dielle Dias

Another important aspect various athletes in American Top Team use is the design and organization of the annual program. According to the current literature, there are many preparation phases and models, but in this book, we are going to describe the program that we use at American Top Team the most.

We may highlight five basic preparation phases (mesocycles): the initial conditioning phase (anatomical adaptation), hypertrophy phase, strength phase, power phase, and MMA circuit (power endurance) (Dias, et al. 2017). In each phase, we normally train for four weeks when we have sufficient time, but at the top level, the athletes fight on average every three months or less, which obliges us to shorten or remove some phases. For example, veteran UFC athlete Gleison Tibau does not perform a hypertrophy mesocycle, because he normally weighs 84 kilograms (185 lb), presenting between 8 percent and 10 percent body fat, and he fights in the 70 kilogram (155 lb) division. Accordingly, all his work is based on “getting the weight down,” which is not at all easy because he is extremely strong and has practically no extra fat to burn.

As we can see, the annual program may vary according to each athlete and should always be designed backward. Thus, we note the date of the fight and count how many weeks we will have until the day we can start the training program. We then plan how many mesocycles will be performed and the priorities and duration of each one. On average, we need 12 weeks (three mesocycles of four weeks) to train an athlete and one final week to “make weight” and achieve supercompensation.

The time that remains between a given fight that has just taken place and the signing of the contract for the next fight is distributed less strictly. There are “only” six to eight sessions of training during the week, with most sessions focusing on the fighter’s initial conditioning (anatomical adaptation). There is an emphasis on learning new techniques based on the athlete’s deficiencies (Dias, et al. 2017).

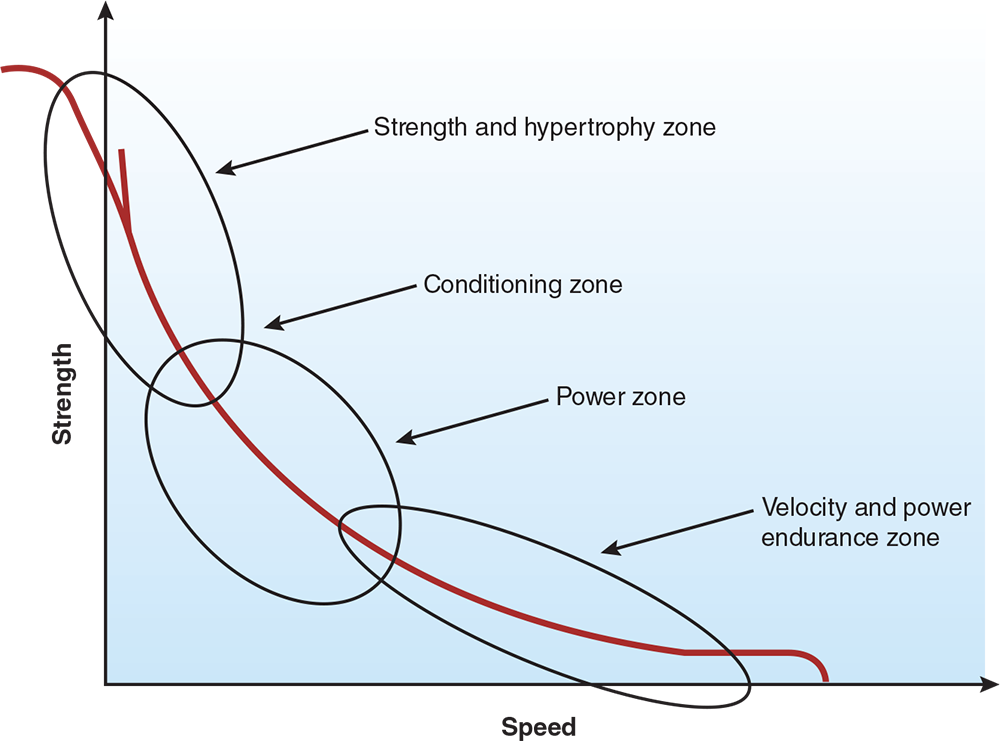

An effective way to understand and justify the system we use in the periodization of our athletes is combining this model with the famous strength versus speed curve. The curve illustrates the inverse relationship that exists between strength and speed. In other words, the higher the load, the slower the movement, and the heavier the training, the slower the speed. Based on this concept, if we need to develop the physical quality of strength, we should train on the left side of the curve. To develop speed, we should stay on the right side. In figure 1.27, we can see the strength versus speed curve and the training zones.

Based on the strength versus speed curve, Dr. Joseph Signorile of the University of Miami developed a way to work all the phases of training: “Surfing the curve” was how he described figure 1.28, and according to Juan Carlos Santana from the Institute of Human Performance, this is the best way to understand and justify the correct use of training periodization.

Adapted from Santana (2007).

To “surf the curve,” we must start in the middle (initial conditioning), head upward and to the left to create muscle hypertrophy and develop strength, and then we gradually “surf” down the curve (toward the right) to work on power and speed.

The strength versus speed model explains how to divide the five phases of training, but, as mentioned, in the training program for athlete Gleison Tibau and other athletes of American Top Team, there is no desire to increase lean mass, because they normally fight in a division below their normal body weight. This obliges us to reduce the number of phases and remove the hypertrophy phase from the macrocycle. The total program ends up with 17 weeks, in which we use four weeks of training in each phase and the last week to make weight and achieve supercompensation.

More Excerpts From Training and Conditioning for MMASHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?