Common deviations from ideal alignment

This is an excerpt from Safe Dance Practice by Edel Quin,Sonia Rafferty,Charlotte Tomlinson.

The ribcage sits directly above the pelvis in efficient alignment. The shoulders should be horizontally level and relaxed, with the arms able to hang freely. On inhalation, the ribs widen and the abdominal muscles lengthen, and on exhalation, the ribs return and the abdominal muscles shorten (Haas, 2010). It is often difficult for dancers to understand how to find the engagement of the core muscles to provide support and keep the ribs relaxed - sucking in the belly too much leads to inefficient breathing patterns and tension in the ribcage. The stability of the shoulder girdle is essential for lifting and partnering activities. Dance styles that use balance in inversion or frequently support the weight through the arms should ensure a strong and secure upper body. Regardless of whether the upper body is used for weight bearing, every dance style incorporates a specific and expressive use of the arms, often with intricate choreography, such as in classical Indian dance and flamenco, which need control.

The thoracic and especially the cervical spine are vulnerable if not kept in alignment. Any weight bearing on the head and loading on this part of the spine is risky. General advice in sport is that overextension of the cervical spine can cause many problems, including compression of intervertebral discs and pinching of arteries and nerves at the base of the skull. However, full neck and head rolls, now seen as a contraindicated movement, are still included in some dance vocabulary. For example, whipping the head (and hair) is commonly seen in commercial and street dance choreography. Given the repetitive nature of dance training, the implications are obvious. Teachers and choreographers should seriously consider the use of head rolls in their vocabulary and should never use them in warm-up, substituting simpler up-and-down or side-to-side head movements instead.

When the shoulder blades (scapulae) wing - that is, the internal border can be seen sticking out away from the body - this is associated with muscle imbalance, especially a tight pectoralis minor and weakness of the muscles mentioned earlier that assist scapular stabilisation. The same can be said for protracted (rolled forward) shoulders. The shoulder blades should also not be pinched together. Ideally they should lie flat against the ribcage. The cue ‘squeeze your shoulder blades together' to correct forward shoulders or kyphosis and to generally encourage upright posture or arm placement is unhelpful, and it can cause many repercussions in the upper spine. Another frequent misalignment is lifting the ribcage up and forwards, often as a compensation for an anterior pelvic tilt (Welsh, 2009). This can be a result of misunderstanding the cue ‘pull up'.

Dancers need to be able to lift the arms without disturbing the centre, losing balance or increasing tension in the shoulder or back (Franklin, 2012). Each dance genre requires a specific and precise styling of the arms in space or strength and control in weight bearing. As dance forms have developed, modern choreography has led to increased strain on the shoulders and arms, with the integration of more athletic and gymnastic movements and amount of floor work needing upper body support (Simmel, 2014). For many styles, the goal is to find a secure positioning of the arms in which the torso is also neutralised and stabilised (Clippinger, 2016).

One of the most common directions given to dancers is ‘hold the arms on the back.' The meaning behind this is to encourage the most efficient muscular action to stabilise the arms, so the technical directions should explain how to do this effectively. If the dancer does not understand the mechanics, the primary result is tension in the upper body. The muscles that connect the arms to the back are concerned with scapular stabilisation (the serratus anterior, the rhomboids, the lower trapezius and the latissimus dorsi). It has been observed that dancers tend to be weak in these areas (Haas, 2010). A balanced use of these muscles makes the arms feel like they are coming from the back (Howse & McCormack, 2009). Problems arise when excessive tension and stress in the trapezius causes lifting of the shoulders (scapular elevation), which makes an efficient use of the arms difficult. If the arms are held too far behind the body when they are out to the sides (for example, in second position, used in many styles), this can cause excessive arching of the lower back and protruding ribs. If they are too far forward, this results in a closing in of the chest and a kyphotic posture (Clippinger, 2016).

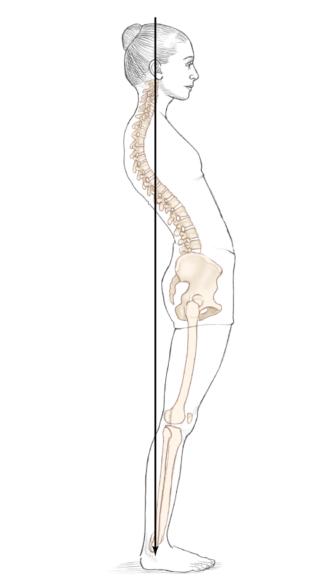

To conclude this section on common deviations from ideal alignment, fatigue postureshould also bementioned. This posture requires less energy to stand than normal, and is a common unconscious adaptation in all dancers, even those who are highly experienced (Clippinger, 2016). For example, the dancer rests on the ligaments in the hip joints by pushing the pelvis forward considerably (increasing the posterior tilt) and hanging back in the upper torso (see figure 2.13). It is relaxing for the muscles, but puts a strain on the overstretched hip joints because the body's centre of gravity runs behind the pelvis (Simmel, 2014).

Fatigue posture.

Similarly, it is quite common to see dancers alternating between different postures in a dance session, their everyday habitual stance and their dance alignment. Dance-specific posture is assumed during practice, but in the relaxed moments - for example, when listening to feedback, observing other dancers in class in moments of rest or even interacting socially in rehearsal - the dancer can slip into an unstable pose, reinforcing detrimental postural habits. This may involve sitting into the hips, leaning backwards in the upper torso, rounding the shoulders forward with the hands on the hips or shifting the weight habitually to one leg. Like all deviations, these habitual postures have detrimental effects. Teachers should bring these habits to the dancer's attention to encourage conscious employment of the necessary muscles (spinal extensors and hip flexors) at the appropriate level of contraction to remedy them. Conscious awareness of posture, even in normal movement such as sitting, standing or lying down, will help the dancer to maintain a healthy body that supports the demands of dance techniques more effectively.

It is also worth mentioning at this point that, for some dancers, regularly carrying their own kit and costumes in heavy dance bags can place added strain on the body, causing muscle imbalances and postural changes over time. Recommendations are to use bags that spread the load as evenly as possible, choose padded handles or shoulder straps or consider wheeled suitcases that allow a neutral standing posture to be maintained (SHAPE, 2002).

Dancers could be more aware of, and leaders should discourage, slipping into fatigueor relaxedposture, both in and out of the dance session. Slumping, sitting in the hips or habitually releasing the weight into one hip while resting places increased stress on ligaments and joints and does not support the development of good dancing alignment.

Common Upper Body Alignment Issues

- Shoulders: Rolled forward or elevated

- Shoulder blades: Winging out

- Ribcage: Lifted or protruding in front

- Arms: Held too high (lifted shoulders) or too far back

Alignment Cues for the Upper Body in Dancing

Problems in the body

- The front of the ribcage lifts up or pushes forwards and the shoulder blades pull back as the dancer tries to stand up straight. The abdominals cannot engage properly, and the dancer experiences difficulties with breathing effectively as well as reduced mobility and increased tension.

- The shoulders are raised and tense or rolled forward and the shoulder blades wing out.

- The arms are held too far behind the ribcage, causing excessive arching in the lower back and lifted ribs in front.

Helpful and unhelpful cues

- Avoid saying, 'open your chest', 'lift your chest', 'pull your shoulders back/down', ‘pinch your shoulder blades together' and 'push your arms down in the back.'

- Instead, encourage dancers to relax the lower ribs so that the shoulder girdle sits freely on top of the ribcage. They should relax the shoulder girdle at a point close to the spine rather than forcefully pushing the outer edges of the shoulder down. Prompt them to release the shoulder blades downward and outwards, as the shoulders widen to the sides, emphasising the scapular adductors and the thoracic spine extensors. Direct dancers to lightly pull the arms down before they are raised. With the arms held out to the sides, if the shoulder joint is centred, the hands should be visible out of the corners of the eyes.

Imagery tips

Encourage dancers to do the following:

- Imagine the shoulders suspended from the neck like the sails of a ship, with the spine as a mast and the shoulder girdle as a cross-beam suspended from it.

- Imagine the shoulder blades sliding down the back and crossing into the opposite trouser back pockets.

- Imagine your armpits are deep and soft. They are filled with small balloons that inflate as you inhale and deflate as you exhale.

Learn more about Safe Dance Practice.

More Excerpts From Safe Dance PracticeSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- Women in sport and sport marketing

- Sport’s role in the climate crisis

- What international competencies do sport managers need?

- Using artificial intelligence in athletic training

- Using the evidence pyramid to assess athletic training research

- How can athletic trainers ask a clinically relevant question using PICO?