Understanding the International Classification for Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model

This is an excerpt from Recreational Therapy Assessment by Thomas K Skalko,Jerome Singleton.

By Thomas K. Skalko

Understanding the ICF Model

To apply the coding of the ICF for effective service delivery, one needs to first understand how to utilize the ICF as a means to classify the full functioning of the individual, perhaps beginning with a diagnosis from the ICD-11 (see www.who.int/classifications/icd/revision/icdprojectplan2015to2018.pdf?ua=1). The ICD-11 is a medical coding system for documenting diagnoses, signs of illness, symptoms of a condition, and social circumstances. Unlike the ICF, which focuses on functioning, the ICD offers some insights into the etiological classification by diagnosis of health condition, disorder, or disease. Coupled with the ICF, both classification schemes offer a relatively full picture of the medical and biopsychosocial aspects of the individual (Stucki, 2012).

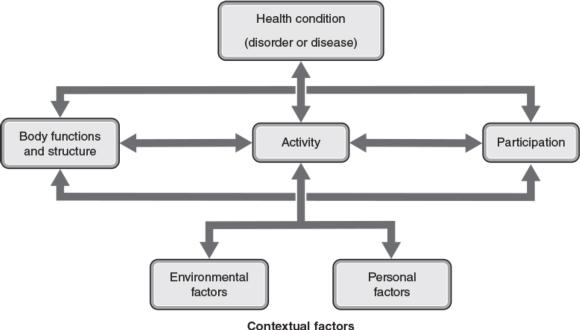

Because this chapter focuses on understanding the ICF and demonstrating its connection to assessment, a full understanding of the ICF is of value to the reader. The ICF is a hierarchical structure consisting of two parts, each with two components. Part 1, functioning and disability, is broken into the components (1) body functions and structures, and (2) activities and participation. Part 2, contextual factors, is broken into (1) environmental factors and (2) personal factors. (Note: Types of personal factors are identified for clarity but are not classified, because every person has unique personal factors and the classification of every person's personal factors would be impossible.) In the ICF, "Each component (except personal factors) can be expressed in both positive and negative terms" (WHO, 2001, p. 10).

The ICF

domains are classified from body, individual and societal perspectives by means of two lists: a list of body functions and structure, and a list of domains of activity and participation. In the ICF, the term functioning refers to all body functions, activities and participation. The term disability is similarly an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. The ICF also lists environmental factors that interact with all these components. (WHO, 2002, p. 2)

The ICF is

a classification of health and health-related domains—domains that help us to describe changes in body function and structure, what a person with a health condition can do in a standard environment (their level of capacity), as well as what they actually do in their usual environment (their level of performance). (WHO, 2002, p. 2)

Let's break down these concepts in order to better understand the ICF. The ICF model, as shown in figure 3.1, offers a coding system that begins with the recognition of a health condition. As delineated in the ICF, a health condition (disorder or disease) generally affects some physical (biological) or functional aspect of the individual's body structure or body function. Changes or impacts on body structure-for example, a spinal cord injury, limb amputation, or even pregnancy or aging-may affect an individual's functioning in multiple domains. The affected body structure or function affects the activities and participation of the individual in the life of the community. In addition, environmental factors contextually affect the individual in a positive (facilitator) or negative (barrier) manner. Remember, since every person is unique, the ICF does not include personal factors in the classification system but does provide examples of factors to consider.

Figure 3.1 The ICF model.

Adapted by permission from International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, pg. 18, copyright 2001 (Geneva, World Health Organization); Adapted from B. Prodinger et al., "Toward the ICF Rehabilitation Set: A Minimal Generic Set of Domains for Rehabilitation as a Health Strategy," Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 97, no. 6 (2016): 875-884.

The impact on body structure and body function has implications for the ability of the individual to engage in activities (execution of a task) and participation (engagement in the life of the community). It is important to note that the community may range from the broader environment (e.g., city or neighborhood) to home or residential facility.

Unlike what one may perceive from the term activities (e.g., a recreational event), activities under the ICF are more discrete. Activities within the ICF refer to the specific execution of a task like manipulating objects (i.e., holding a pencil), focusing attention, or walking on different surfaces. Participation, on the other hand, may include moving around within a facility or using transportation. Together, the concepts of activities and participation are a bit different within the ICF model than how they are often used within recreational therapy practice. In recreational therapy service delivery, we often think of an activity as a game or manual arts project or exercise in a group. In the ICF model, as noted, an activity may be grasping an object, balancing on a foot, or making a decision. If a consumer cannot grasp a paint brush, they will not be able to participate in a painting experience or event. Therefore, participation in a community art class may not be possible unless the therapist assists the consumer in acquiring the skill of grasping or making a modification. So, it is important to note that the ICF classifies the functional performance of the discrete tasks or actions needed to participate in life situations. As therapists, we want to be able to assess one's functioning in such discrete tasks so that we can improve the functioning, design adapted supplies, or modify the activity to enhance engagement (participation).

In addition to body structure, body function, and activities and participation, environmental and personal factors also affect the functioning of the individual. Environmental elements include products and technology, natural environment and human-made changes to the environment, support and relationships, attitudes of others, and services, systems, and policies. The qualities (or lack thereof) of the environment, including technology, affect the ability of an individual to address functioning (e.g., a prosthetic device) and, therefore, engagement in the life of the community (see figure 3.1). Remember that personal factors, such as gender, ethnicity, religious beliefs, cultural morays, and family upbringing, are not coded because every individual is unique.

To understand the model, a brief description of each element is of value. Table 3.1 offers an explanation/definition of each component of the ICF (Rauch, Luckenkemper, & Cieza, 2012; WHO, 2001). Unlike earlier linear models of disability, the ICF model is a dynamic and interactive model that reflects the functioning of the individual and recognizes the impacts of each element in an individual's life. Each component interacts with the other components depicting this dynamic relationship. For instance, when an individual's body structure is changed, there is a subsequent impact on body function, activities, and engagement in the life of the community. When an individual engages in an activity that improves body function or structure, there is a resulting impact on activities that may also affect participation in the community. The ICF is about classifying functioning and includes those environmental factors that can facilitate functioning and engagement or serve as barriers to one's functioning.

The following sections offer a brief explanation of each element of the ICF. It is important to recognize the dynamic relationship between each element and the resulting positive or negative impact on an individual. The health condition has an impact on body structure, body function, activities, participation, and environment functioning, each altering the functioning of the individual.

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?

- How do hormones affect muscles?

- Machine learning: The cornerstone of data-driven decision making for sport organizations

- Examples of how systematic reviews and meta-analyses are used in sport