Traditional Face-to-Face Versus E-Leadership

This is an excerpt from Leadership in Recreation and Leisure Services by Timothy S O'Connell,Brent Cuthbertson,Terilyn J Goins.

In the technology-rich environment in which we live, our key interpersonal and professional encounters are not likely to be solely face-to-face or virtual. Rather, our relationships exist on a continuum between more or less virtual. Some of us believe that virtual encounters, via Facebook, MySpace, Skype, FaceTime, and the like, enhance our already established relationships. On the other hand, Instagram and Twitterare encounters experienced almost exclusively online, such as IT specialists who contract their services to institutions and perform the majority of their work within the online environment. In exclusively online encounters, face-to-face interactions are supplemental and secondary to the online experience.

As the world grows smaller through technology-driven globalization, questions emerge about the effectiveness of traditional face-to-face leadership models within the virtual environment. In face-to-face interactions, participants enjoy a complete communication experience, along with an immediacy that gives them a chance to reflect, seek feedback, and respond based on the information obtained. Furthermore, the immediacy of face-to-face encounters fosters a sense of aliveness and community that has to be manipulated and created in situations in which people are separated by time, culture, and distance (Kerfoot, 2010). E-leaders, in contrast to traditional leaders, enact their leadership roles in virtual networks such as e-mail, instant messages, videoconferences, webinars, FaceTime, Google Hangout, and Skype. Although such technologies provide quick access to a lot of information and a vast array of communication venues, they can also create feelings of anxiety as a result of information overload (Avolio & Kahai, 2003; Belanger & Watson-Manheim, 2006).

Because of the apparent interpersonal disconnectedness the virtual environment affords, it is natural for e-leaders to focus more time on tasks than relationships. This, of course, is a grave error because rapport, cohesion, and trust are essential to virtual team success. An absence of relational connection can result in increased interpersonal conflict, which inhibits productivity (Bergiel, Bergiel, & Balsmeier, 2008; Hertel, Geister, & Konradt, 2005; Rosen, Furst, & Blackburn, 2007). Unfortunately, the nature of the virtual environment makes it difficult for leaders to recognize such conflict and address it in a timely fashion. Because of factors such as culture, time, and space differences, along with divergent levels of technological expertise, e-leaders also have difficulty succinctly articulating a vision, a mission, and objectives to virtual participants (Dewar, 2006), which, in turn, potentially squelches feelings of unity and enthusiasm.

Although some leadership behaviors are equally important in face-to-face and virtual settings, evidence suggests that certain actions are more important than others depending on the degree of virtualness. For example, in highly virtual environments, participants believe it is important for leaders to establish a clear and common understanding of tasks, "focusing on outcomes and deliverables rather than on team members' activities" (Zimmerman, Wit, & Gill, 2008, pp. 328-329). Additionally, they suggest that leaders establish and maintain relationships in a time-efficient manner, avert misunderstandings, ensure that everyone feels a part of the team, be sensitive to cultural diversity, and emphasize shared values among team members (Walvoord et al., 2008).

Consider the job of educators offering courses that are administered entirely online. To accomplish similar goals online to those achieved in face-to-face classes, instructors must meticulously measure their words, communicate more frequently, read between the lines students write, engage each student individually rather than as a part of the class, and constantly reassure students that they can succeed in the course. In essence, because there are limited opportunities to engage students as a group within the virtual environment, instructors must work much harder to reach a goal that's comparatively simple to attain in person. Additionally, when a misunderstanding, miscommunication, or conflict occurs in the virtual environment, it takes significant time and effort to repair the damage, and sometimes it's not even possible to do so.

Because people in a virtual setting often have little to no firmly established interpersonal connection to those who lead them, it is all too easy to assign negative or dishonest motives when things go awry. Quashing those attitudes, once in motion, can be quite the feat for even the most experienced leaders.

Leadership Within a Virtual Environment

Without question, leading in online environments presents greater challenges than leading in face-to-face environments. Computer-mediated communication is here to stay; thus, it is essential to consider strategies to enhance the online leadership process. It should be obvious by now that the area in need of the most work within the virtual environment is the interpersonal, relationship dimension of the communication process. When people feel valued, they produce, regardless of the communication medium. Following are some suggestions for improving performance and satisfaction in computer-mediated situations:

- Establish a clear set of rules regarding communication behaviors - how frequent, how much, and to what extent (Lin, Standing, & Liu, 2008).

- Set consistent meeting times for the group as a whole, and connect via other media whenever possible, such as FaceTime, telephone, Skype, and chat sessions (Cascio, 2000).

- Create an easily accessible central databank of information for participants (Hertel, Geister, & Konradt, 2005; Powell, Piccoli, & Ives, 2004).

Also, if at all feasible, as early as possible in the process, virtual participants should meet face-to-face, even if it is only once. When virtual groups meet face-to-face, they more readily establish essential interpersonal connections and develop the rapport, respect, and trust they need to carry them through the assigned project(s). Because the focus within the virtual encounter tends to be task oriented, face-to-face meetings should concentrate on relational development among participants and ironing out any existent or potential misunderstandings or conflict issues (Hertel, Geister, & Konradt, 2005; Lantz, 2001; Powell, Piccoli, & Ives, 2004).

Leadership Within a Hybrid Environment (Both Face-to-Face and Virtual)

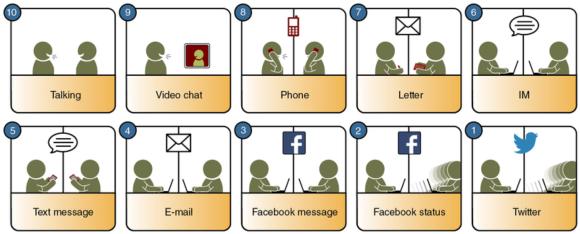

Although computer-mediated communication is best suited for certain tasks, such as passive, informational, and nonsocial tasks (e.g., brainstorming), the optimum situation in which to lead is a combination of virtual and face-to-face encounters. When both are used, the task and interpersonal demands can be met with greater ease, thereby enhancing overall productivity. For instance, instructors of hybrid courses that combine virtual and face-to-face instruction do not have to scrutinize every word, nor do they need to expend as much effort to meet every student's need. Face-to-face instruction enables them to cover a topic or address an issue once rather than have to repeat it a number of times, depending on the number of student inquiries. Additionally, impressions of e-leaders tend to be more accurate when interpersonal connectedness is established in the face-to-face encounters. As figure 3.3 illustrates, relational depth tends to function on a continuum of least intimate to most intimate based on degree of face-to-face encounters.

Ten dimensions of intimacy in today's communication.

Reprinted, by permission, from J. Lee.

Advantages of Face-to-Face Communication

For a number of reasons, face-to-face communication may be superior to mediated communication. Face-to-face communication is more nonverbally substantive; and the communication experience is more comprehensive. It presents a stronger social, emotional, and cultural context and is generally less stressful than computer-mediated communication (Daft & Lengel, 1984; Hancock, 2004; Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976; Sproull & Kiesler, 1986; Thompson & Coovert, 2003; Walther, 1993). Additionally, when the other person doesn't respond in a virtual environment, you can never be totally certain of whether the person received the message or is simply ignoring you. Unfortunately, this phenomenon often elicits a number of not-so-positive assumptions that can later backfire (Bergiel, Bergiel, & Balsmeier, 2008; Dewar, 2006).

Imagine a situation in which a coworker attempts to contact you via e-mail to discuss an important issue and you don't receive the message. In the absence of a response, your coworker assumes that you are ignoring the message and complains to your boss. The boss subsequently calls you into her office to address your apparent apathy. You're completely taken by surprise because you never received the e-mail, which you tell your boss. The misunderstanding is resolved and the meeting is scheduled. The incident would never have happened had your coworker simply followed up with a telephone call or office visit.

It is possible to avoid such unnecessary communication mishaps by adhering to a few simple e-mail etiquette rules:

- Never use e-mail to address emotionally charged or sensitive issues that are better communicated face-to-face. E-mail should primarily be reserved for exchange of information.

- E-mail the person back within 24 hours of the time the message was sent to you.

- Stay away from flashy colored and patterned backgrounds because they can distract from the message conveyed.

- Avoid using all caps in your e-mail response because it can come across as yelling.

- After a couple of responses on an issue, you need to change the subject of your e-mail. Don't have 20 e-mails referencing an issue that was resolved 15 e-mails back.

- Run a spell-check and then read through your response thoroughly to ensure that it doesn't contain major grammatical errors. If you write Susan went to there house, the spell-checker will not catch this error because the word there is spelled correctly (the correct word is their).

- If you haven't heard back from the person in 72 hours, send a follow-up e-mail to check the status of your original e-mail. If you still receive no response, you may have to resort to picking up the telephone. This will alleviate any unnecessary, and probably inaccurate, assessments about why the person has not responded to your e-mail.

The immediacy of face-to-face encounters creates a strong sense of community and vibrancy that is often difficult to negotiate in computer-mediated environments.

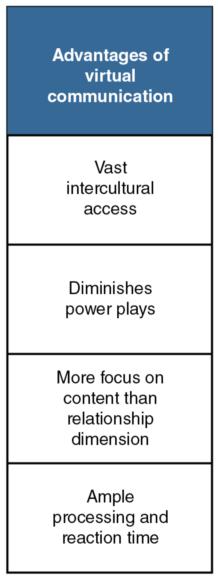

Advantages of Virtual Communication

Although mediated communication introduces chellenges that can typically be avoided in face-to-face encounters, it is not without advantages. We can now interact with people across the globe, which introduces cultural exposure beyond what we could ever have imagined. We can reconnect on Facebook with people we haven't seen or heard from in years; we can have virtual, face-to-face encounters, via FaceTime, Skype, or Google Hangout, with friends and family who live across the globe or across the street; we can play games with complete strangers; we can even meet and court people we've met only over the Internet.

Many people report that the virtual communication experience has actually improved the quantity and quality of their relationships with others, resulting in more regularly scheduled and substantive contact time (Boase et al., 2006; Dainton & Aylor, 2002; Wellman et al., 2008). Moreover, the absence of the visual component in many virtual encounters tends to create an equalizing effect and openness among participants that may not exist in face-to-face encounters. Visual cues available face-to-face tend to highlight features we use to discriminate against one another, such as sex, race, attractiveness, body size, age, and physical limitations. The virtual environment, on the other hand, diminishes such power plays, encouraging inclusiveness, respect, and affinity. Put another way, computer-mediated communication focuses more on the content dimension of the interaction and less on the relationship dimension, or at the very least redefines it. In virtual communication, absent the visual display, there is no race, sex, ethnicity, religion, and social or cultural status. It is pure, unadulterated human-to-human contact. See figure 3.4 for a visual depiction of the advantages of face-to-face and virtual communication.

Advantages of face-to-face and virtual communication.

Whether face-to-face or virtual, the communication process is complex. For it to succeed, all participants must fully commit to the experience. In face-to-face interactions, it is necessary to confront issues as they emerge, which doesn't always allow for sufficient processing time before forging ahead. Virtual communication, on the other hand, gives participants a chance to step away from the situation, reflect on what's happening, and carefully respond after thinking things through. In any case, it is essential to consider the purpose of the interaction and select the medium of communication that best suits that purpose and can accomplish established goals.

Learn more about Leadership in Recreation and Leisure Services.

More Excerpts From Leadership in Recreation and Leisure ServicesSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?