The Creative Process

This is an excerpt from Choreography 4th Edition With Web Resource by Sandra Cerny Minton.

Choreography, or dance making, is a creative process that requires practice as well as knowledge of how the process functions. It was once a popular notion that creative work was driven by divine intervention and that only certain people had the ability to create. Fortunately, today we understand that although people differ in their capacity for creative work, anyone can benefit from and enjoy creating.

Creating is not something that takes place only in the heads of special people; anyone is capable of doing creative work. However, creativity should refer to an action or idea that is new and also socially valuable; it is an interaction between a person's thoughts and social and cultural contexts (Csikszentmihalyi 2013). Creating is not easy, but knowledge of creative problem-solving strategies will enable you to work through blocks that may arise.

Traditionally, creativity is described as a five-stage process. During the first stage, the person who is creating prepares by becoming immersed in content that arouses interest, evokes curiosity, or presents a problem to be explored. In the second stage, incubation, the creative problem is put aside and ideas germinate or churn below the conscious level of thought. It is likely that unique and interesting connections are made during this stage. The third stage in the creative process is sometimes called the aha experience. It is the moment of insight when the pieces of the puzzle suddenly appear and fall into place. During the fourth stage, soul searching is necessary as is evaluating whether the insights discovered are valuable. This stage requires sifting through the movements created to determine which ones merit development. In the fifth stage, the person who is creating elaborates on inspired content. This stage occupies the most time and requires the hard work of making choices and decisions and of translating inspired content into words, an invention, a painting, or, in our case, movement (Csikszentmihalyi 2013).

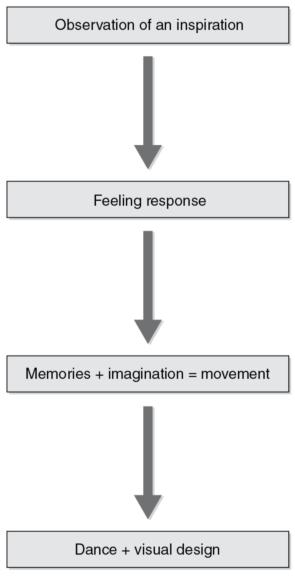

Choreography has its own and somewhat parallel creative stages. One could say a dance evolves through the following process, which is used throughout this book:

- Observing an inspiration: During this stage, the choreographer notices something: an object, idea, or event that sets the dance-making process in motion. Anything can be used as an inspiration - parts of the environment or works of art, including poetry and music.

- Feeling response: The choreographer feels and has a response or emotional reaction to the inspiration that he or she would like to portray in a dance.

- Using memories and imagination: Almost simultaneously, the choreographer pulls from memories and imagination to help improvise movements to be used in the dance. During this phase, there may be aha experiences during which movements suddenly come into being, or the choreographer may put improvisation aside, allowing incubation to occur before continuing the movement discovery process.

- Evaluating the movements: The choreographer must decide whether the movements fit the intent of the dance and where and how they contribute to the development of the work.

- Enhancing the dance through visual design: The choreographer can enhance the dance through choices in visual elements such as costumes, lighting, props (object separate from costume, but part of actions or spatial design in dance), and technology, although technology is sometimes an integral part of the creative process.

Figure 1.1 represents a visual framework (the limits in which creation occurs) for the creative movement and dance-making process discussed in this book. According to this framework, the choreographer must first carefully observe (notice or view with attention) aspects of the inspiration for a dance. Those who have researched and written extensively about how highly creative people think note that active observation, a trait of great artists, means taking time to look repeatedly and carefully (Root-Bernstein and Root-Bernstein 1999). After observing, the choreographer experiences feelings or a response to an inspiration. This response is combined with memories and images (mental pictures or bodily feelings) and transformed into movement. Later, these movements can be modified and molded into a dance that is performed and appreciated.

Figure 1.1 Linear framework for the creative movement and dance-making process.

Another recommendation for doing creative work takes into consideration the feeling component. You must be passionate about whatever you are creating. Passion fuels the creative process and propels it through difficult stages when it seems the end product will never be realized. It also enables you to develop strategies and put in the hard work necessary to achieve your goal (Kaufman and Gregoire 2015).

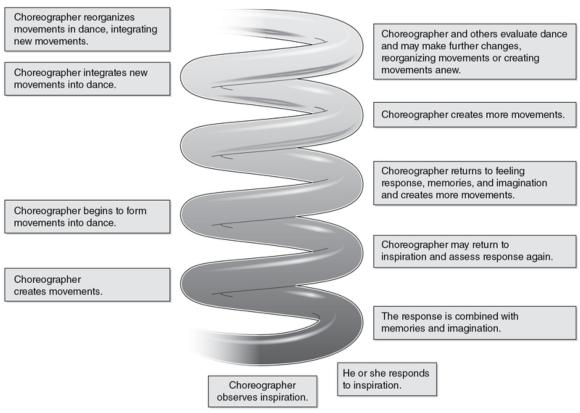

Something is amiss in the previous description of the dance-making process because it is not linear as depicted in the diagram, but instead is more fluid, proceeding both forward and backward. Because the choreographer moves back and forth within the process, movement creation, elaboration or variation of those movements, and their evaluation are frequently interrupted by a return to periods of added observations, insights, memories, and further analysis of the response to the inspiration. New feelings may arise, suggesting new directions for developing a dance, so earlier stages are revisited. This means dance making is a cycling, ever-evolving process. The creative process is recursive because the elaboration stage can be interrupted by periods of incubation or fresh insights; the incubation stage might even last for years before a solution is realized (Csikszentmihalyi 2013).

A more realistic model for movement discovery and dance making is shown in figure 1.2. The first four steps in the choreographic process - observation, feeling response, memories combined with imagination to equal movement, followed by evaluation - can be revisited as the choreographer cycles back and forth through various stages. The final steps of shaping and arranging movement and incorporating visual design elements are discussed in chapters 2, 3, and 4. The visual design aspects may evolve throughout the process or be added when the dance is complete.

Figure 1.2 Dance making is a spiraling, circular progression in which the choreographer intermittently returns to beginning steps when needed.

Learn more about Choreography, Fourth Edition With Web Resource.

More Excerpts From Choreography 4th Edition With Web ResourceSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW