Six facets of the Power Yoga for Sports system

This is an excerpt from Teaching Power Yoga for Sports by Gwen Lawrence.

This is an excerpt from Teaching Power Yoga for Sports by Gwen Lawrence.

Over the course of creating Power Yoga for Sports, I boiled its effectiveness down to six components: balance, strength, flexibility, mental toughness, focus, and breathing. Each component has been carefully thought out and is pivotal to athletes' ability to reach their potential. In baseball, a great player is called a five-tool athlete; in Power Yoga for Sports, I teach the six tools. No single tool can create excellence on its own; they build on each other, and at different times athletes must focus on different areas to improve. Yoga is not just all about stretching.

Balance

Balance can be understood in two ways: in terms of dynamic equilibrium and in terms of the body's symmetry and alignment. Following the Power Yoga for Sports program and following routines laid out in this book, an athlete will develop better proprioceptive, physical balance. You can simply think of this form of balance as your ability to maintain your base of support. In physics and in art, a line of gravity is used to define balance. Improving your balance involves improving your ability to keep your line of gravity over your base of support by shifting an imaginary plumb line from your chin (if standing) directly over the base of support.

Balance in relation to Power Yoga for Sports is the ability to move your body accurately and efficiently while playing your sport. It also involves being agile enough to change position on a dime without falling or losing your bearings.

Balance and Your Body's Sensory Systems

Maintaining balance requires the coordination of three different sensory systems in your body: the vestibular system, the somatosensory system, and the visual system.

Vestibular System

The vestibular system consists of the sense organs in your head, specifically your ears, which regulate your equilibrium and give your brain directional information about head position and change of position and about your movement in relation to what is moving around you. The best thing you can do to improve this system is go barefoot as much as possible, as is done in yoga. A common practice in yoga to improve balance is to use drishti, or a point of focus, in which you rest your gaze on a chosen point during yoga practice and movement. Focusing on a fixed point improves your concentration in a game situation because it's easy to become distracted when your eyes are moving around to take in your surroundings or to monitor the actions of your opponent. Drishtis also help in establishing proper alignment.

Somatosensory System

The somatosensory system comprises nerves called proprioceptors in your muscles and joints along with the pressure and vibration sensors in your skin and joints. These receptors are sensitive to stretch or pressure in the surrounding tissues. With any movement of the legs, arms, hands, or other body parts, sensory receptors react by carrying impulses to the brain to maintain balance and prevent a fall. You can observe this in yoga. Have you ever tried a warrior 3 pose and felt the constant and subtle actions of all the small muscles in the foot and ankle as you held your position? Try right now to simply stand in a quiet room in mountain pose with your arms down by your sides and your eyes closed. Notice the vacillations in your feet; that is the somatosensory system at work. To improve it, regularly practice your yoga, giving special attention to balance poses on one foot. (See standing poses in chapter 5.)

Visual System

The visual system relies on your eyes to figure out where your head and body are in space and your location in space relative to other objects or players on the field. To help improve your vision, you should limit the time you are exposed to blue light interference from sources such as a TV or computer. Avoid eyestrain as much as possible; for example, read in proper lighting, and allow your eyes to rest for six to eight hours a night. You need to have good eyes, good ears, and healthy muscles and joints to be properly balanced. One practice for improving the visual system is to vigorously rub your hands together until they become hot, then lean your elbows on a table and cup your hands over your eyes. In my experience, this practice allows the healing heat to penetrate the eyes, then the optic nerve, and eventually the brain to relax and release tension.

When you take care of your vestibular, somatosensory, and visual systems and follow the Power Yoga for Sports routines, your movements become smoother and easier. This will help you to become more effective at your sport. Working on balance will certainly help you on the field. Your body must be able to support compromising positions that your sport puts you in. If you have better balance, acrobatic plays will be commonplace for you; your performance will improve, and you will have less risk of injury.

Balance and Symmetry of Your Body

The second part of balance, and the one that is more important to the Power Yoga for Sports system, is symmetry of the muscles and the alignment of the body, taking into consideration all external bumps and torques. Most sports are one-side dominant: You throw from one side, your kick strength is stronger on one side than the other, your serve is one-side dominant, and so on. The sport that may be the most innately symmetrical is swimming. Each of us has a dominant side, so you can never be perfectly symmetrical. However, with careful mindfulness and body awareness, you can become immediately aware when you are too far off balance. Power Yoga for Sports can teach you to understand asymmetries and address them before they become imbalances. Be proactive in preventing injury, rather than reactive in recovering from injury.

Think of it this way: Symmetry problems are like caring for a car. If you never rotate the tires on your car, you may end up driving on a misaligned car with a balding tire that eventually ruptures. Or think of a monster truck—those absurdly large trucks with extremely large tires to match! Now imagine replacing the passenger-side tires of that monster truck with tires meant for a small two-door sedan. Sounds ridiculous, right? It is the same with your body. Unfortunately, we are often more careful with our cars than we are with our own bodies. Imagine the damage the monster truck would sustain to the undercarriage and how terribly it would drive. I see people walking around every day with absurd misalignments in their bodies, and it pains me.

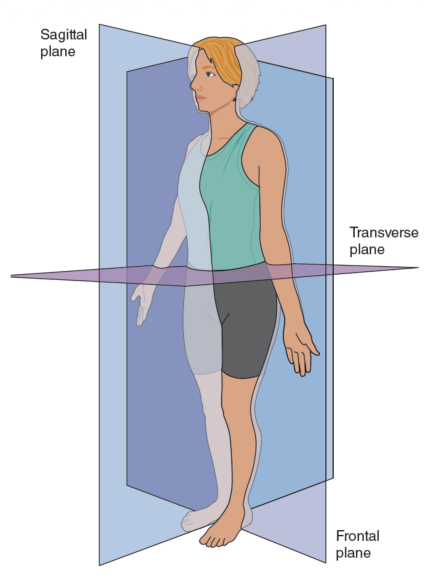

To help athletes to address their imbalances, you must understand the planes of the body and their relation to movements. Figure 1.1 shows the three planes the body moves in—sagittal, frontal, and transverse. If you take into consideration imbalances, tight spots, knots, and excess scar tissue in conjunction with these planes of motion, I believe it will be easier for you to understand why asymmetries can cause the body to move awkwardly and, even worse, to incur tears and strains.

Figure 1.1 Three planes of motion: sagittal, transverse, and frontal.

Take a look at the sagittal plane, which slices the body in half down the middle to create a perfect right side and left side. This is the plane in which the body performs flexion and extension, such as bending forward or extending into a backbend, and the even more detailed flexion of the knees and front of the shoulders. When you look at the body and visualize the sagittal plane, you can better identify left- and right-side imbalances that are out of the ordinary. You can also visualize all the movements done on the sagittal plane that must not cross the cut wall—for example, kicking the leg straight out in front, not across the body because that movement would break through the wall.

Next, recognize the frontal plane. The frontal plane divides the body into a front and a back. This is not symmetrical like the sagittal plane (the front of your body looks different than the back of your body), but you can spot asymmetry here when you see people who are too far forward on their feet and overload the front or too far back and overload the back. You can also identify imbalance here if you see someone with poor posture and a hunched back. The frontal plane is where the movement of abduction (moving away from the midline) happens—for example, performing a side kick or raising your arm straight out to the side. The body also adducts (moves back toward the midline of the body) in this plane; squeezing your inner thighs together or bringing your arms toward the body are examples of adduction.

Finally, we analyze the transverse plane. This plane separates the body at the waist to form a top body from the waist up and a bottom body from the waist down. This plane is an important one for athletes because the transverse plane is where rotation of the spine occurs. Every sport requires athletes to twist their bodies to generate torque or to create a large field of vision. If you do simple seated twists, you can immediately notice which side you twist toward more easily and which side presents more resistance.

Movement in the transverse plane can seriously affect your level of play. For example, imagine you are running toward the goal in a soccer game while dribbling the ball in front of you. You move effortlessly to the left, but you are more limited in your ability to rotate to the right. In this case, you might lose some field of vision on the tight side, and opponents might sneak up on you more easily from this side and steal the ball. Opposing coaches can pick this out on films of your performance, and they can target your weak right-side skills as vulnerability. Power Yoga for Sports can help you to address these asymmetries and make corrections so you can excel. This idea comes back into play when we discuss the importance of eye dominance and symmetry of the eyes in chapter 2.

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?