Origins of Musical Theatre Dance

This is an excerpt from Beginning Musical Theatre Dance With HKPropel Access by Diana Dart Harris.

The first dramas that included music and dance were presented by the Greeks in the 5th century BCE. Those dramas served as models for the Romans, who expanded the dance element. During the Middle Ages, groups of traveling actors used dance to tell stories, and during the 12th and 13th centuries, the Catholic Church staged dramas that included music and dance to reinforce morality lessons and bring Biblical stories to life. As the Middle Ages ended and the Renaissance began, Greek dramas were resurrected. Some of these dramas, like Monteverdi's Orfeo (1607), which was performed at the Gonzaga court, and Purcell's Dido and Aeneas (1689), which was performed in England, featured dance and movement sequences. Pantomime performances were also popular and included singing, acrobatics, clown acts, and dialogue as well as dance. The dancing included in these pantomimes was considered show dance and could be anything from classic hornpipe dances to tightrope dancing. Additionally, dance was used between acts of Shakespearian plays and was used to entertain audiences between the acts of John Gray's The Beggar's Opera in 1728. These dances usually featured an individual dancing alone or leading a group of dancers who performed some type of Scottish folk dance.

A recreation of a Greek games dance.

Did You Know?

The Romans created the first tap shoes by nailing bits of metal to the soles of their sandals so that the dance steps could be heard.

Musical Theatre Dance in Colonial America

Across the ocean in colonial America, theatre was kept alive by British acting troupes. The Beggar's Opera, which premiered in Europe in the 1720s, was New York's first documented musical performance in 1750. In 1767 the Theatre on John Street opened and became a main performance space in New York for the remainder of the 18th century. The comic opera The Archers, performed there in 1796, is considered the first American-born musical (Kenrick, 2011). During the Revolutionary period in America (1764 - 1789), some members of the Continental Congress voiced their opposition to theatres and play-going because those pastimes were considered scandalous and distasteful (Kenrick, 2011). This opposition led to several of the 13 colonies banning public performances, but try as people might, keeping others from dancing is difficult, and even legislation could not stop it. Between 1750 and 1843, white men in black face traveled around the country, performing songs and dances in circuses and as entertainment during play intermissions (Kenrick, 2011). These intermission performances eventually developed into full-length minstrel performances in the mid-1800s.

Minstrelsy and Vaudeville

Minstrel shows were black song and dance parodies born when traveling blackface performers named themselves the Virginia Minstrels and presented a full-length show in 1843. But those minstrel shows were not allowed on Broadway, which was considered New York's cultural center and was meant for the elite citizens who enjoyed operas and plays. The minstrel shows were performed at the Bowery, which was where the lower class gathered. During the minstrel era, which lasted into the early 1900s, dance steps were officially given names that were written down.

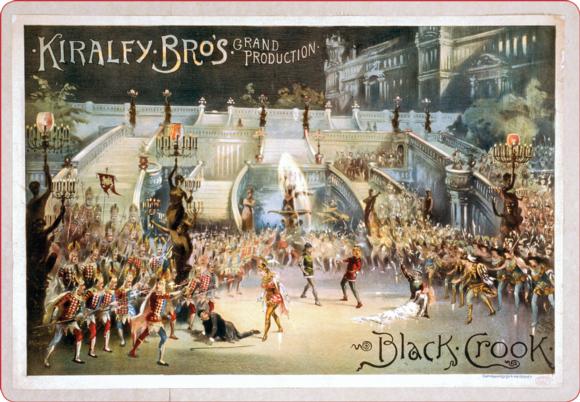

In 1866 a production called The Black Crook was scheduled to be performed in New York at Niblo's Garden. Meanwhile, a Parisian ballet company had been booked to perform at the Academy of Music. A fire at the Academy of Music led to a merger of the ballet performance with the production of The Black Crook. The result was a 5 1/2-hour play with added songs and dances. The songs and dances had no relationship to the plot, making the production a circus-like spectacle that showcased individual dancers wearing only tight-fitting bodices and tights. The Black Crook was the first production in the United States to run longer than a year, and it marked the birth of musical theatre in the United States.

The final scene from The Black Crook.

The Black Crook paved the way for the burlesque and vaudeville shows of the late 1800s. The burlesque shows of this decade featured women who wore costumes that showed the shapes of their bodies. Their performances entertained the middle and lower classes and used music and dance to mock operas, plays, and the upper-class socialites. Vaudeville shows were a series of unrelated acts as part of an evening's entertainment that ignited interest in all kinds of dance, including Irish dance, clogging, tap, comic dancing, acrobatics, fancy dancing, skirt dancing, and toe dancing. Vaudeville was the training ground for people who would go on to perform in and create the Broadway musicals of the 20th century.

Did You Know?

The toe dancing done in vaudeville shows was very different from classical ballet dancing en pointe. It involved the dancers doing tricks, like jumping rope, while dancing on their toes. Some dancers even attached metal to the tips of their shoes to tap out rhythms while dancing.

Ballroom, Ragtime, and Chorus Girls

In the early 1900s, ragtime music, which combined European folk songs with West African drum rhythms, found its way onto the theatrical stage. The dance portions of performances began to expand. Dance directors gained recognition and focused on how the stage could be used and how the dances looked from an audience perspective. Additionally, dance instructors spent a lot of time training dancers to perform in specific ways. When Vernon Castle (1887 - 1918) and Irene Castle (1893 - 1969) refined and polished the dances that the black population had been doing to ragtime music, ballroom dancing was born. The Castles were responsible for making ballroom dance popular and altering those social dances to make them interesting for an audience to watch.

In the early 1900s, John Tiller (1854 - 1925) founded a school in London, England, that offered dance training to women, who became known as London's Tiller Girls. They were trained to perform in unison, to march in military formations with military precision. Tiller provided dancers for London's revues and musical comedies and brought girls to the United States to dance in vaudeville shows and musical plays like The Man in the Moon (1899) and The Casino Girl (1901). As time passed, he added can-can kicks and vaudeville-type steps to their training. Similar schools soon opened in the United States.

Ned Wayburn (1874 - 1942) founded the Studio of Stage Dancing in 1905 in Manhattan and created kick lines. Although he believed that all dancers needed to be trained, his first priority was appearance. Dancers were chosen for shows because of their beauty, and he was the first dance director to demand that all the dancers in his chorus line be the same height.

His dances contained intricate, fast steps, and he demanded musicality and smiles. Wayburn effectively used tableaus, or groups of posed, still dancers, to depict scenes on the stage. He was probably the most influential, successful, and best-known dance director of his time, acting as dance director for the Ziegfeld Follies, an annual show produced by Florenz Ziegfeld (1867 - 1932) from 1916 through 1919 and again from 1922 through 1923. He is credited with developing the Ziegfeld walk, which required the dancers to walk down stairs balancing enormous headpieces by simultaneously thrusting one hip forward and pushing the opposite shoulder forward.

A Ziegfeld Follies performer from 1925.

Also known for their work on the Ziegfeld Follies were dance directors Julian Mitchell (1854 - 1926) and Albertina Rausch (1891 - 1967). Mitchell expanded on Tiller's idea of the chorus girl and developed the concept of a grand production number. Mitchell was responsible for the dancing in both The Wizard of Oz in 1902 and Babes in Toyland in 1903.

Albertina Rausch was the third dance director of the Ziegfeld Follies. She brought elements of her classical ballet training to Broadway by combining ballet arm movements, or port de bras, similar to those used in classical ballet, with less stylized movements and by combining the eccentric vaudeville toe dancing with Tiller precision. She set this dancing to modern music and called it American ballet (Kislan, 1987).

Meanwhile, in Harlem, black musical theatre was also flourishing. Opening in 1911, The Darktown Follies was an all-black musical featuring a circle dance that involved everyone snaking around the stage with his or her hands on the hips of the next person in line. This circle dance was purchased by Florenz Ziegfeld to be used in his Follies. In 1923 the show Runnin ' Wild reached back to the Ashanti dancers of Africa and featured one of their dances on stage, called the Charleston.

Lines between black and white musical theatre began to blur as the whites began to borrow more black dances and perform them on white stages.

During this period, dance went from being an accompaniment for stage plays to earning a featured place on the stage. Thanks to The Black Crook and notable dancers like the Castles, Ned Wayburn, Julian Mitchell, Albertina Rausch, John Tiller, and Florenz Ziegfeld, dance began to earn a more prominent place in performances.

Learn more about Beginning Musical Theatre Dance.

More Excerpts From Beginning Musical Theatre Dance With HKPropel AccessSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW