Marketing and Motivational Strategies for Early Stages of Change

This is an excerpt from Fitness Professional's Handbook 8th Edition With HKPropel Access by Barbara A Bushman.

By Janet Buckworth

The goal of fitness professionals may be to help people maintain regular exercise, but they may also be called on to promote regular exercise to people who are inconsistently active (i.e., preparation stage) or have not yet considered starting a fitness program (i.e., precontemplation stage). For example, the primary goal of a media campaign may be to capture the attention of inactive people and motivate them to contemplate beginning an exercise program or another healthy behavior. This might involve putting informational prompts at the point of decision to act, such as hanging catchy posters next to elevators encouraging people to take the stairs (9) (see figure 22.1). Bulletin boards, pamphlets, fliers, handouts, websites, and social media with upbeat information about the benefits of exercise and practical suggestions for increasing physical activity also can catch the attention of potential exercisers. Handing out passes at local restaurants for an aerobics class is a proactive form of recruitment. Fun runs and walks supporting charities may motivate people who primarily want to help the organization to begin thinking about exercise for its own sake. Wellness fairs, HRAs, and fitness testing in communities and at work sites also can prompt contemplation and enhance motivation to become more active.

To increase participation in the early stages of behavior change, the fitness professional’s role is to provide education about benefits of being physically active, to describe how to exercise sensibly, and to offer encouragement to follow through with a personal exercise program. Specific strategies to increase adoption and early adherence are recommended (1, 5):

- Ask participants about their exercise history. They may need accurate information to dispel myths (e.g., the myth of no pain, no gain) and to develop positive attitudes about exercise.

- Explore ways exercise can benefit them personally. Find out what they think they will get out of being physically active, and provide information and resources about additional benefits.

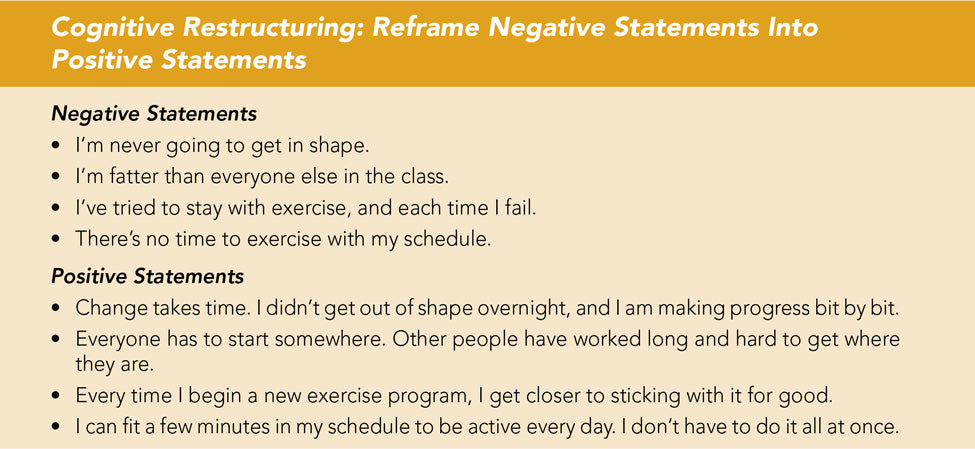

- Help participants develop knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and skills to support the behavior change. In addition to providing information and training in self-management skills, the fitness professional may use cognitive restructuring to identify discouraging thoughts and replace them with positive statements (see the sidebar Cognitive Restructuring: Reframe Negative Statements Into Positive Statements).

- Bolster the participant’s exercise self-efficacy and sense of competency with success-producing learning experiences. Four sources of information contribute to self-efficacy beliefs and can be addressed by the fitness professional:

- Mastery experiences: These experiences include behavioral rehearsal with proper supervision and positive feedback. The fitness professional can make sure participants have chosen activities that are appropriate for their fitness and skill level so they can experience a sense of accomplishment when they exercise. Practical feedback also will help participants be successful and thus feel more confident. Additionally, an increased sense of competency is motivating. Everyone likes to do things they are good at!

- Verbal persuasion or self-persuasion: Suggesting to people that they can succeed in behaviors they have not been successful in previously and giving specific feedback to help enhance their skills and foster success will promote self-efficacy. The fitness professional can provide verbal encouragement and teach participants positive self-talk.

- Modeling: Observing others can serve as a guide to performing a specific behavior. When people see someone successfully doing what they have little confidence to do, they start to expect that they, too, can succeed. The fitness professional can set up situations in which participants see someone like themselves succeed (e.g., post a newspaper story about seniors who now exercise regularly) or watch a peer who has trouble with the task succeed (e.g., point out to a new participant that an established exerciser “also had difficulty jogging 3 miles when they first started the program, but after months of hard work, they reached their goal”).

- Interpretations of physiological and emotional responses: Physiological arousal associated with a behavior can be stressful and contribute to lower self-efficacy for that behavior. The typical increased heart rate, respiration, and muscle tension that occur during exercise may make novices feel anxious or uncomfortable and less confident. The fitness professional can make sure that participants have information about the normal physiological responses to exercise and know how to interpret their physiological responses accurately.

- Clarify expectations, and make sure they are reasonable and realistic. Use guidelines for goal setting to ensure initial successes.

- Identify potential barriers to behavior change and brainstorm with the participant about ways to overcome these barriers. Barriers can be personal (e.g., low exercise self-efficacy), physical (e.g., past injuries), interpersonal (e.g., peer pressure from sedentary friends to engage in sedentary behaviors instead of exercising), or environmental (e.g., inclement weather or lack of a safe place to walk). For example, one person may want to exercise but does not have access to facilities and another person may think they do not have the willpower to stick with a program. The first person would be helped with a home exercise program, whereas the second would benefit from social support and reconsidering discouraging thoughts.

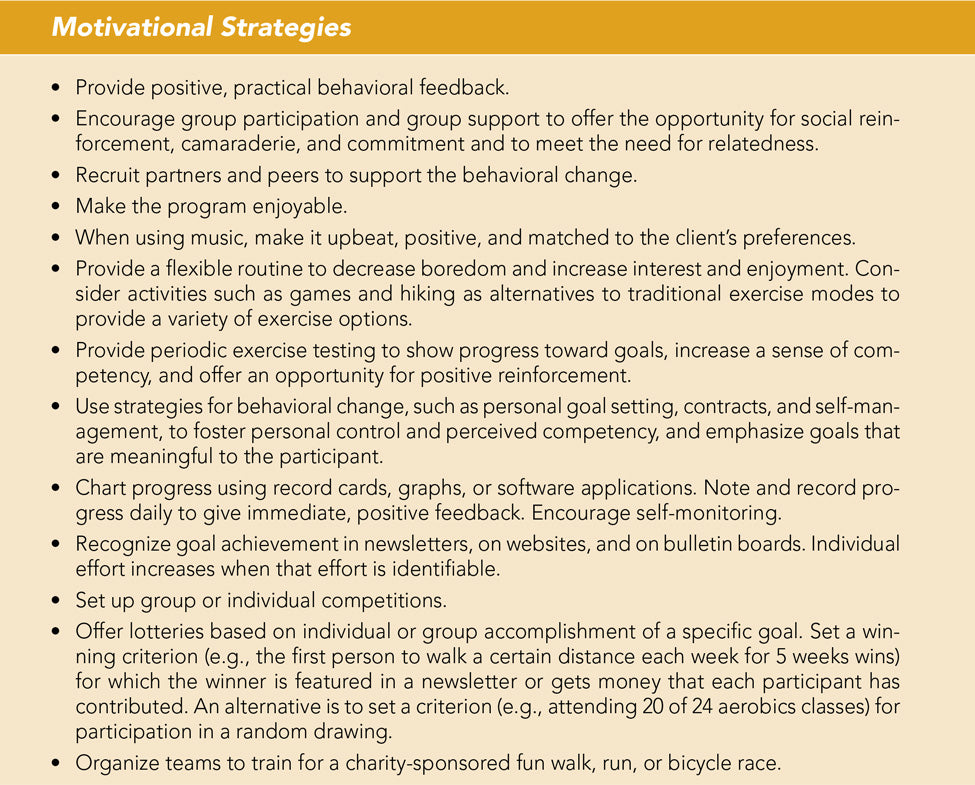

- Foster motivation to adopt and maintain an exercise program. Set up incentives to exercise. Incentives can be tangible (e.g., T-shirts, certificates, water bottles, recognition on a website) or intangible (e.g., sense of competence, enjoyment). Tangible incentives are useful early in a program, but intrinsic motivation is associated with better adherence (23). Offer a variety of incentives, but focus on fostering more intrinsic and self-regulated motivation, such as a sense of accomplishment or enjoyment. Strategies to increase motivation are listed in the sidebar Motivational Strategies.

Key Point

Individual, social, and environmental factors motivate people to move from not thinking about starting an exercise program to setting up a plan to begin. A variety of strategies can be used, from mass-media campaigns to fitness testing, to motivate people to move from contemplation into the preparation and action stages. Six strategies to facilitate adopting and maintaining exercise are to

- ask participants about exercise history and use this information to set up a personalized plan;

- help participants develop knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and skills to support behavior change;

- bolster self-efficacy;

- involve participants in setting clear and realistic goals;

- identify and address personal and environmental barriers to change; and

- foster multiple motivators for exercise that have purpose and meaning for participants.

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- Using double inclinometers to assess cervical flexion

- Trunk flexion manual muscle testing

- Using a goniometer to assess shoulder horizontal adduction

- Assessing shoulder flexion with manual muscle testing

- Sample mental health lesson plan of a skills-based approach

- Sample assessment worksheet for the skill of accessing valid and reliable resources