Eating Disorders

This is an excerpt from Medical Conditions in the Physically Active 4th Edition With HKPropel Access by Katie Walsh Flanagan,Micki Cuppett.

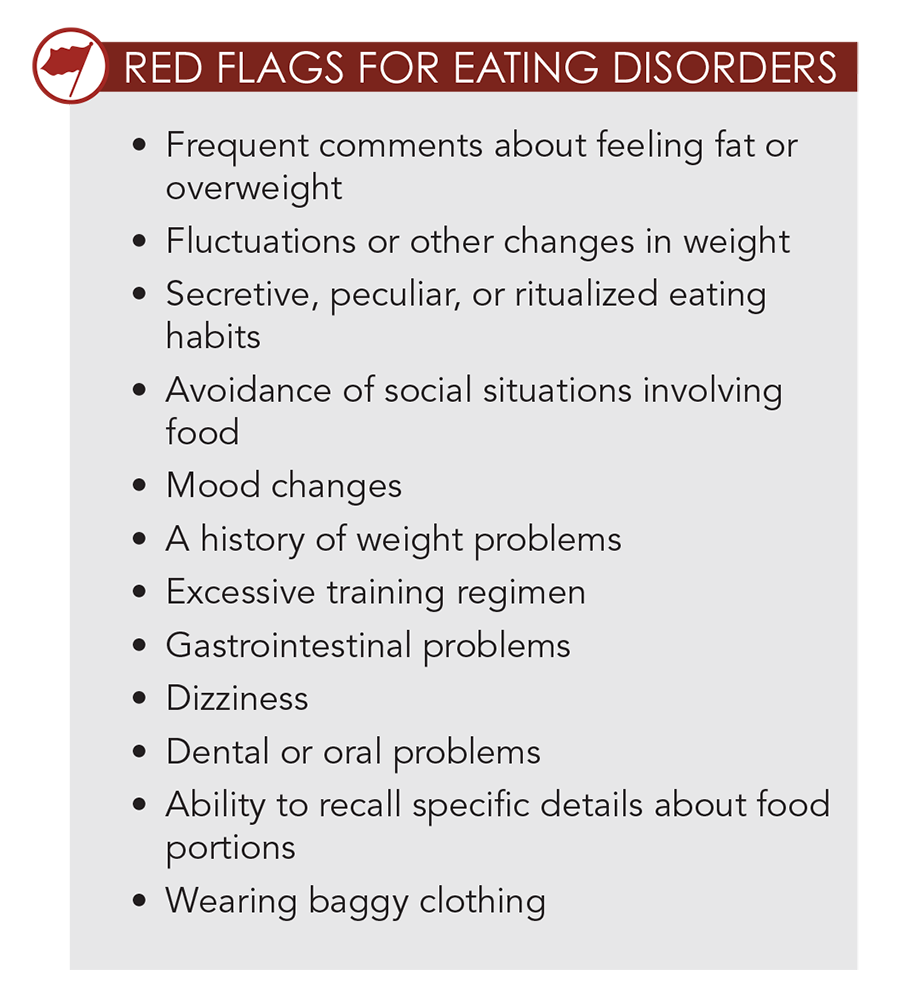

It is estimated that eating disorders affect 8.5% of women and 2.5% of men and that nearly 30 million people in the United States have an eating disorder. Perhaps this is because Americans have a love-hate relationship with food and their bodies. They are surrounded by cheap, high-calorie foods that contain generous amounts of fat and sugar. A growing focus on fitness and healthy lifestyles is paired incongruously with record levels of obesity and related health problems, such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and stroke. The resulting disordered patterns of eating often have their onset in childhood and early adolescence. This is a time when individuals becoming increasingly aware of themselves and attuned to peer group messages about acceptability, attraction, and competence.

Even though athletes are usually more physically active and fit than the average person, the demands of performance, such as maintaining a certain body weight or proportions, can strongly affect their approach to food. Wrestlers, gymnasts, dancers, and swimmers are especially prone to developing problems with food and weight. The estimated prevalence of eating disorders among athletes is up to 45% in women and up to 19% in men. This is considerably higher than in nonathletes, especially within the “lean sport” types.

Like the other issues discussed in this chapter, disordered eating can be viewed on a spectrum of severity. People with these problems often do not fit into clear-cut categories.

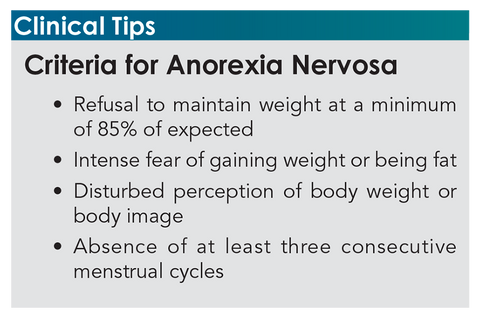

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is a potentially life-threatening condition with long-term mortality rates approaching 20%. Anorexia develops when the person restricts or otherwise compensates for eating to the point that the person drops below 85% of ideal body weight. An important point for athletic trainers to consider is that overtraining is a common compensatory behavior.

Anorexia is a relatively rare condition, with about 5 to 10 new cases per 100,000 people each year and a prevalence of 0.5%. Most cases of anorexia are found in females, but approximately 10% to 15% of cases occur in males. Anorexia occurs more often in industrialized than in nonindustrialized societies. The two subtypes of anorexia are the restricting type and the binge eating–purging type. Individual patient behaviors may vary from time to time.

The possible physical sequelae include gastrointestinal problems (stomachache, diarrhea, constipation, heartburn), amenorrhea or other menstrual irregularities, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, bradycardia, hypotension, decreased muscle mass and body fat, musculoskeletal injuries, lowered core body temperature, development of lanugo hair on the body, and fatigue and weakness. Emotionally and mentally, people develop a distorted body image, emotional lability, cognitive rigidity, perfectionist attitudes, social isolation, an intense fear of becoming fat, and eventual impairment of mental functions. Concomitant psychiatric diagnoses are significantly more common in persons diagnosed with anorexia nervosa.

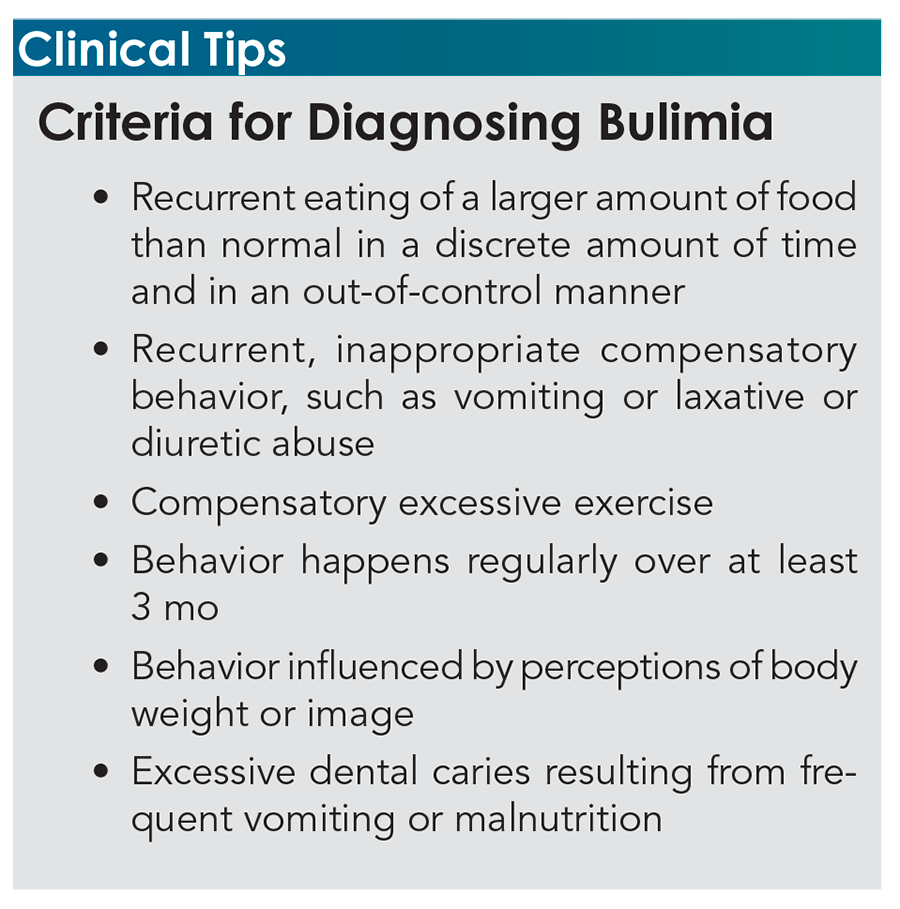

Bulimia

Bulimia is another type of eating disorder that affects athletes and physically active individuals and is more common than anorexia. Even though the athlete is often at or slightly above normal weight, bulimia can also be life-threatening. It is characterized by binge eating followed by an inappropriate compensatory act designed to prevent weight gain and, perhaps more importantly, to combat the person’s sense of being out of control. These compensatory acts include restricting food (dieting or fasting), vomiting, laxative or diuretic use, and exercise. A stereotypical binge involves eating large amounts in secret in a short period of time. In fact, people may or may not be especially secretive, and the amount of food constituting a binge is a matter of perception. People with bulimia who believe they have eaten too much may see even one too many cookies or slices of pizza as a binge. In response, they engage in one or more compensatory behaviors.

The results of this behavior include fluid and electrolyte imbalance, gastrointestinal difficulties, inflammation of the esophagus and parotid glands, dental conditions, visual disturbances, muscle weakness, and menstrual irregularities. Vomiting, laxatives, or diuretics usually are what cause the problems. From psychological and behavioral points of view, people with bulimia often exhibit excessive concern about body weight and shape, irritability, social withdrawal, depression, and impulsive behavior.

Binge Eating Disorder

A third category is binge eating disorder. Considered to be the most common eating disorder, it is characterized by eating in binges that result in emotional or physical discomfort similar to bulimia but without the obvious compensatory behaviors mentioned previously.

Treatment of Eating Disorders

Eating disorders of all types require a thorough assessment and interprofessional treatment. This treatment can be done on an outpatient basis, but inpatient stabilization may be needed for more serious problems that create life-threatening electrolyte imbalances or starvation. The athletic trainer should have an identified team in place for expediated referral and patient-centered treatment. The most effective treatment teams include medical, nutritional, and mental health practitioners. The antianxiety and depression medications described previously are used to treat underlying or comorbid conditions (see table 17.3 on medications). These medications are especially useful in treating the dysphoria associated with low self-esteem and disturbed identity, the anxiety that comes with changed eating behaviors (e.g., eating but not purging, fear of gaining weight), and the obsessive–compulsive nature of the disorder.

Group therapy—or more generally, milieu therapy—can help the patient to confront unrealistic expectations, maladaptive behaviors, and distorted thinking. Nutritionists work with patients with eating disorders to help them gain a more realistic understanding of the body’s physiology and nutritional needs and to establish expectations about diet and exercise. Individual and family therapy is especially helpful with children and adolescents, and it addresses dysfunctional social, cultural, and family dynamics within which eating behaviors are often embedded.

SHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?