Classical Ballet in Russia

This is an excerpt from History of Dance 2nd Edition With Web Resource by Gayle Kassing.

"It is not so much on the number of exercises, as the care with which they are done, that progress and skill depend."

August Bournonville, Etudes choréographiques

Classical music, art, and ballet have much in common and yet many differences. What makes each art form classic? Was it the historical time in which the artwork was generated? Was it the form the artist used to create it? In the second half of the 19th century, visual arts styles went through romanticism, realism, impressionism, symbolism, and postimpressionism movements. Music for most of the 19th century, however, remained in a romantic period from the late works of Ludwig van Beethoven to the impressionist composers such as Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. The classical era in music ranged from the second half of the 18th century through the first two decades of the 19th century. For ballet, the last quarter of the 19th century became the classical era in Russia; Swan Lake is the prototype of a classical ballet. As chief architect of the classical ballet, choreographer Marius Petipa took elements from romanticism, which he expanded and wove into fantasy plot lines, while adding pointe work and partnering. His legacy of ballets has survived and continues to be reconstructed, restaged, and reenvisioned by great ballet companies and artists throughout the world.

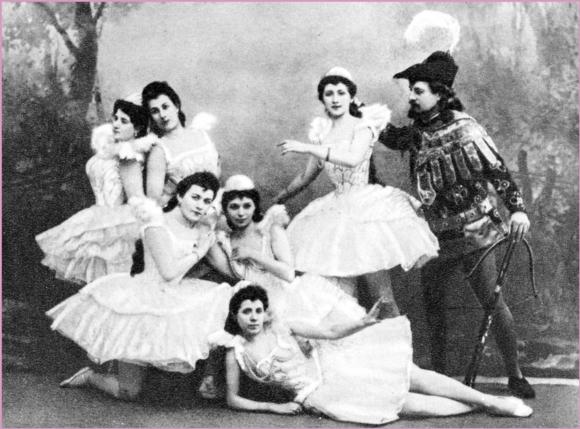

Swan Lake (1895), the prototype of classical ballet.

Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Importing European stars of technical prowess and commissioning music to match his choreography, Petipa sculpted ballet into a classical form. His resources were prodigious, with highly trained dancers and the finest decor, costumes, and music at his command. His works were performed in one of the world's greatest theaters and the production expenses were underwritten by the czar.

Ballets expanded in extravagance to become entire evenings of entertainment. They featured dazzling ballet technique and national dances interwoven into a dramatic story told through stylized mime scenes, all supported by beautiful music, expensive costumes, and elaborate scenery. The female ballerina still dominated the stage, with the male dancer as her partner. The leads were supported by a hierarchy of dancers, including a large corps de ballet.

Glance at the Past

During the second half of the 19th century, Italy solidified as a country and Prussian nationalism and power expanded under Bismarck into a unified Germany. In England, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert kept the far-flung British Empire under their guidance. At the French court, Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie ruled over the Second Empire until the 1870s. And in the United States, tensions mounted quickly into the Civil War, followed by years of reconstruction and the advent of industrialism.

History and Political Scene in Russia

Since Catherine the Great's reign, Russia had been under an autocratic rule that dominated the nobles, who in turn ruled the serfs. In 1825 reformers wanted Nicholas I to ascend the throne under a constitutional monarchy, but that effort was squashed. Alexander II abolished serfdom in 1861. During the last half of the 19th century, Russia became more industrialized and expanded its power west to Afghanistan, China, and the Pacific. The completion of the Trans-Siberian Railroad linked Europe and Asia. When Nicholas II ascended the throne in 1894, a governmental reform movement was afoot, with his reactionary ministers setting the path to revolution in the next century.

Society and the Arts

Although Russia was distant from European cities, ambassadors visited the French court as early as the 17th century, then brought the latest fashions and dances home with them. Throughout the 18th century Russian aristocrats emulated French style and arts and spoke French. Russia was locked in a feudal system headed by a powerful nobility with vast land holdings. In isolated country estates, nobles had their own theaters in which serfs provided the talent for entertaining the noble family and guests.

Russia's Age of Realism began in the second half of the 19th century. Novels such as Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace and Anna Karenina revealed the dark side of Russian society.

Dancers and Personalities

Ballet in the last half of the 19th century was dominated by the development of classical ballet in Russia. While in European and American theatres, ballet moved into entertainment forms, touring companies, and vaudeville.

Dancers and Choreographers

The dancers and other personalities were not all Russian; many were European, and choreographers and teachers were predominantly male. The ballerina remained the center of attention with her technical feats en pointe and was supported by male dancers in pas de deux.

Arthur Saint-Léon (1821 - 1870)

A French dancer, choreographer, violinist, and composer, Saint-Léon was considered one of the best dancers of his time, with extraordinary ballon (effortless, suspended jumps) and elevation. His dancing took him to theaters in London and throughout Europe. In 1845 he married ballerina Fanny Cerrito. He worked as a ballet master throughout Europe and was appointed company teacher at the Paris Opéra in 1851, where he created many of the divertissements for various productions. He developed a notation system that he published in 1852.

From 1859 to 1870 Saint-Léon succeeded Perrot as ballet master of St. Petersburg's Imperial Theatre, where he choreographed new works and restaged others, often including national dances in his ballets. During this time, his duties there were such that he was able to divide his time between St. Petersburg and Paris. His ballet Coppélia (1870) remains in ballet repertories today.

Marius Petipa (1819 - 1910)

Marius Petipa was born in France but made his fame in Russia. A son of a French dancer, he and his brother, Lucian, along with other family members, began studying dance with his father. By 1838 Petipa was a principal dancer and had created his first ballet. He studied with Auguste Vestris, traveled to the United States with his family, and danced and choreographed in Bordeaux and Spain. He was acclaimed as a dancer in romantic ballets and often was a partner to Fanny Elssler. In the 1840s Petipa was a principal dancer in Paris. He went to St. Petersburg in 1847, where he danced and assisted Perrot; in 1862 he was appointed ballet master there. His first successful ballet in Russia was La Fille du Pharaon, in that same year.

Marius Petipa.

© Sovfoto.

Over his career in Russia, Petipa created 50 or more ballets. Some are considered classics of ballet, including the following:

- Don Quixote (1869)

- La Bayadère (1877)

- The Sleeping Beauty (1890)

- Cinderella (with Enrico Cecchetti and Lev Ivanov; 1893)

- Swan Lake (with Lev Ivanov; 1895)

One of the first choreographers to work closely with a composer, Petipa collaborated with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky on many ballets. In his collaborations with Tchaikovsky, Petipa would give the composer specific instructions about the quality of the music and other details, such as how many measures of 3/4 time, followed by so many measures for pantomime, and so on. His ballets were spectacles, with lavish costumes and sets in which both ballet and pantomime were used to tell the story, providing an entire evening of entertainment. Petipa included national or character dances in his works. He demanded technically strong ballerinas and premier danseurs (lead male dancers). Imported Italian dancers, including Cecchetti, Legnani, and Zucchi, starred in the classical ballets and provided competition for developing Russian dancers.

Petipa's standards for ballet sent it into its classical era. His attention to dramatic content, form, and music in creating a unified production is what crystallized the form by the end of the century. He has left a legacy of ballets. Today some are performed in their entirety, while only pas de deux or parts of other ballets remain. Petipa created a marriage between Italian and French ballet in Russia, thereby leading ballet into a new style and school, the Russian ballet.

History Highlight

Character dances in a ballet represent a specific national folk dance, using the steps and style of the folk dance but with ballet elements included.

Lev Ivanov (1834 - 1901)

A Russian dancer and choreographer, Lev Ivanov was born in Moscow. He studied ballet in Moscow and St. Petersburg and joined the Maryinsky Theatre's company in 1850. During his career as a dancer, he was admired in character roles. In 1885 Ivanov choreographed a new version of La Fille Mal Gardée, his first full ballet, and then other works. When Petipa became ill, Ivanov choreographed The Nutcracker. For a benefit for Tchaikovsky, he choreographed the second act of Swan Lake. Petipa was so impressed that he mounted the entire ballet with Ivanov, allowing him to create the second and fourth acts, in which the swans dance.

Ivanov is considered by many to have been a sensitive artist with a keen vision and poetic style. His delicate sense of music still radiates from his work today, and his beautiful choreography in the second act of Swan Lake proves his talent. Unfortunately he remained in the shadow of Petipa throughout his career, his work overlooked by a regime that focused on European talent and leadership.

Enrico Cecchetti (1850 - 1928)

Born in Rome into an Italian dancing family, Enrico Cecchetti was a dancer, mime, and teacher. Most of his career was connected with the Russian ballet, first under Petipa and then under Serge Diaghilev. His development of a daily ballet curriculum is his legacy to modern ballet; he created a logical progression of class exercises and components and balanced the adagio and allegro parts of the class. Cecchetti taught the great dancers of the early 20th century, including Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, Anton Dolin, and Ninette de Valois. After his retirement he moved to London. Prodded by English author and publisher Cyril W. Beaumont and assisted by his student Stanislas Idzikowski, Cecchetti published A Manual of the Theory and Practice of Classical Theatrical Dancing in 1922. This book became the curriculum basis of the Cecchetti Society, which was founded in England to train teachers. Subsequently, branches of the Cecchetti Society were formed in other countries to continue this master's teachings.

Pierina Legnani (1863 - 1923)

Pierina Legnani was born in Milan, where she studied and danced with the ballet at La Scala. She became a ballerina in 1892 and toured Europe, then went to Russia. She appeared in St. Petersburg in 1893, performing her renowned 32 fouettés en tournant in Cinderella (which she had performed the year before in London). In 1895 she starred in Swan Lake, creating the dual role of Odette/Odile and performing its famous 32 fouettés in the third act.

Legnani inspired Russian dancers to emulate her technical feats. Each year she returned to Russia to perform, and she was the only European ballerina to be appointed as prima ballerina assoluta (the highest honor for a ballerina). She created many of the leading roles in Petipa's ballets. Legnani's technique brought a new standard for the ballerina of the classical era, which set the tone for the next century of dancers.

Virginia Zucchi (1847 - 1930)

An Italian dancer who studied with Blasis in Milan, Virginia Zucchi performed in Italy, Berlin, London, and St. Petersburg, where she was a success. A technical dancer of virtuoso skill, she was invited to join the ballet company of the Maryinsky Theatre. Zucchi's work as a dancer and her acting skills contributed to the development of the St. Petersburg Ballet School. She spent many years in Russia, retiring to Monte Carlo to teach. Zucchi's dancing, acting, and technical clarity led the St. Petersburg Ballet School to make greater demands of its dancers in terms of technical perfection. The results of her influence would be revealed in the next generation of Russian dancers.

Dance in Russia

To set the stage for the ascent of ballet to a classical art in Russia, you first need to step back in time to gain a historical perspective of dance in that country before the second half of the 19th century. Russia had a rich dance history. Russian folk dances that had existed since the earliest times never lost their features, despite the country's numerous invasions. These dances were incorporated into Russian ballets. Under the reign of various czars, dance flourished. The first Romanov czar, Mikhail, set up an amusement room - a forerunner of the court theater. Czar Alexi presented the first ballet on the Russian stage in 1673; he had heard from his ambassadors about the entertainments presented in European courts and ordered a performance of "French dancing." The first professional ballet in Russia was produced during the reign of Empress Anna Ivanova in 1736, in the opera The Power of Love and Hate. The dances were arranged by Jean-Baptiste Landé for students from the military academy. Later in the 18th century, Catherine the Great of Russia (1729 - 1796) produced a ballet in 1768 to commemorate her heroic act of being inoculated against smallpox.

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, court theaters were replicated by the lesser nobility, featuring serf ballerinas. Some nobles even had theaters built as separate rooms in their houses or as separate buildings on their estates. In these theaters, serfs performed for their masters and the masters' visitors.

Bolshoi Theatre

Public ballets performed in Moscow can be traced back to 1759. Giovanni Battista Locatelli built a private theater for the performance of operas and ballets, which were similar to those presented at the Russian court. In 1764 Filippo Beccari organized a dancing school at the Moscow orphanage. When he was engaged to train professional dancers in 1773, almost a third of the orphans trained became soloists with professional dancing careers in either Moscow or St. Petersburg. The orphanage ballet school came under the direction of the Petrovsky Theatre.

In 1780 the Petrovsky Theatre was built on the site of the present Bolshoi Theatre. After the Petrovsky burned in 1805, Czar Alexander I established the Moscow Ballet and Opera Theatre as an imperial theater. In 1862 the Moscow Theatre separated from the jurisdiction of St. Petersburg. Opera, ballet, and dramatic theaters in Moscow were influenced by the city's university and enlightened circles of society; thus, in Russian opinion, the Moscow Ballet Theatre had an advantage over St. Petersburg in that it was allowed to develop more freely and was less influenced by the court.

Maryinsky Theatre

Jean-Baptiste Landé was the founder of the St. Petersburg Ballet School, the nucleus of professional ballet theater in Russia under the czars and later to become the Imperial Ballet School. During the reign of Anna Ivanova in the mid-1700s, significant developments took place in Russian ballet. Dance training was included in the military school's curriculum, and Landé established a school at the Winter Palace, which was the direct ancestor of the present Vaganova Choreographic Institute. One purpose of the ballets during the 17th century was to glorify the power of the Russian State. The spectacles ranged from dances in operas to ballet-pantomimes to ballets d'action. They included new ballets as well as restagings of ballets being performed in Europe.

The Maryinsky Theatre was an outgrowth of the court theater in St. Petersburg. Catherine II created the position of the director of the imperial theaters in 1766, whose task it was to bring all of the drama, opera, and ballet training and production under his authority. The Maryinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg was closely associated with the court and included a training school. During the 18th and 19th centuries foreign dance masters continued to visit Russia.

Ballroom Dances of the Second Half of the 19th Century

In the second half of the century many of the dances continued, including the quadrille, polka, and schottische, only to be surpassed by the waltz and the music of Johann Strauss the younger. The galop, a ballroom dance since the 1830s, gained new prominence as the last dance at the ball and galop music accompanied the suggestive can-can dances in which girls kicked spectators' hats off in Parisian music halls (Priesing 1978).

Classical Ballet Forms

The classical ballets, although they had some elements in common, varied considerably. They ranged from two acts (The Nutcracker) to four acts (Swan Lake), and some were even longer, with an epilogue (The Sleeping Beauty). They had both fantastic and realistic story elements and took place in an obscure, earlier time or place.

Character dancers performed a blend of national dances and ballet, portraying a national style. These performances became a major dance component in full-length ballets. For example, Swan Lake contains Neapolitan, Spanish, Polish, and Hungarian dances.

The ballerina and the other female dancers performed en pointe. They wore tutus that ranged from above the knee to mid-calf, depending on the ballet. Male dancers wore tunics or peasant shirts and vests, tights, and either knee breeches or shorter pants. Character dancers wore stylized national costumes, usually with boots.

The ballerina and the premier danseur, along with a hierarchy of soloists and a corps de ballet, told the story through ballet dances, mimed interludes, and character dances. Acting roles were played by retired dancers or those who specialized in mime roles. Throughout the ballet male and female dancers or two characters performed pas de deux, or dances for two. Some dances were performed by members of the corps, and others by specific characters, but the grand pas de deux was reserved for the ballerina and the premier danseur.

The grand pas de deux developed from the pas de deux in romantic ballets, such as the one in the second act of Giselle and others in earlier ballets. Because of the four-act scheme in classical ballets, the grand pas de deux takes place in a later act, such as act III of The Sleeping Beauty. Swan Lake has two grand pas de deux. One is performed by the Prince and Odette in act II and is called the White Swan pas de deux; the other is performed by the Prince and Odile in act III and is called the Black Swan pas de deux.

All grand pas de deux are performed by a male dancer and a female dancer, who performs en pointe. They all have a similar structure, as follows:

- Part I: Adagio. In this first dance to a slow musical tempo, the dancers begin with grandiose bows. As they dance, the ballerina executes supported extensions. The man turns slowly, holding the ballerina as she also turns slowly or promenades on one leg, en pointe, in arabesque or another position. He lifts her in various positions or supports her while she does multiple pirouettes.

- Part II: Female variation. In her solo, the ballerina exhibits her technical virtuosity. The variation includes high extensions and often quick, difficult footwork. Usually it ends with a rapid series of pirouettes, done in a circle or on a diagonal path from upstage left to downstage right, and ending in a pose.

- Part III: Male variation. The male dancer exhibits his virtuosity in a solo that includes beaten steps, leaps, and turns. To complete the variation, he performs multiple jumps and turns that end in a pose, often on one knee.

- Part IV: Finale (coda). The coda is another dance for two, but in a quick, allegro tempo. The male and female dance together, performing supported lifts and rapid turns. Then each one dances one or more solo sections that include displays of their technical virtuosity in showy turns, jumps, and beaten steps. They perform the last part of the dance together.

Significant Dance Works and Literature

The work and influence of people from the romantic era created a bridge to classicism and contributed to the development of classical ballet. In Europe, while ballet became staid as an art form, it migrated into spectacle and entertainment. Meanwhile, ballet in Russia soared to new heights, crystallizing in a classical form. Dance literature continued to expand, trying to capture dance through notation, positioning it within society, and exploring its aesthetic values.

Dance Works

Although the focus of this chapter is on classical ballet, a bridge to this period is Coppélia. Choreographed before the development of classical ballet, its form and subject provide an intermediary link between romantic and classical ballets. In the latter decades of 19th-century Russia, Petipa and his artistic staff churned out ballet after ballet to meet audiences' insatiable appetite for novelty, spectacle, and grandeur. These works, the core of classical ballet, have been handed down from one generation of dancers and choreographers to the next, and are still being produced today.

Coppélia, or The Girl With Enamel Eyes (1870)

Coppélia, choreographed by Arthur Saint-Léon, opened at the Paris Opéra in 1870. Charles Nuitter and Saint-Léon wrote the three-act scenario, basing it on the story "The Sandman" by E.T.A. Hoffman. The ballet is romantic and fantastic. Franz and Swanilda are the romantic couple. Dr. Coppélius, a dollmaker, creates a doll with a soul, named Coppélia. When Franz sees the doll in Dr. Coppélius' shop he falls in love with her, thinking she is alive. Later in the ballet Franz and Swanilda reunite, and the third act is a wedding celebration. This charming ballet is often produced today in various renditions. In some 19th-century versions the role of Franz was played en travesti (by a female). Coppélia has many of the vestiges of the romantic era along with the fantastic elements of the classical period.

The Sleeping Beauty (1890)

The Sleeping Beauty, with choreography by Marius Petipa and music by Tchaikovsky, was based on a French fairy tale by Charles Perrault. Petipa created the scenario, which is presented in three acts (four scenes and a prologue). It was produced at the Maryinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in 1890. The ballet has been considered the high point of 19th-century czarist culture and contains some of Petipa's greatest choreographic ideas, including

- the fairy variations,

- Aurora's variations (including the Rose Adagio),

- character dances,

- the Bluebird pas de deux, and

- the grand pas de deux in act III.

The Sleeping Beauty ballet has had many versions since its first production.

The Nutcracker (1892)

Although Petipa wrote the scenario for The Nutcracker, he became ill and the creation of the choreography fell to Ivanov, with music by Tchaikovsky. This two-act ballet was first produced at the Maryinsky Theatre in 1892.

In the first act, a young girl named Clara receives a nutcracker doll from her godfather, Herr Drosselmeyer, at a family Christmas party. Clara falls asleep and dreams that she defends the doll against the Mouse King, and the doll changes into a handsome prince. He takes her on a journey through a Land of Snow on their way to the Land of Sweets. In act II they arrive in the Land of Sweets; after being welcomed by the Sugar Plum Fairy, Clara and the prince are entertained with a series of divertissements. The Sugar Plum Fairy and her cavalier perform for them a grand pas de deux. Little beyond the original grand pas de deux has survived in this popular ballet, which is produced yearly at Christmas in many versions.

Swan Lake (Lac des cygnes ) (1895)

An early version of Swan Lake was incompletely and unsuccessfully produced at the Bolshoi in 1877. It was re-created in 1895 by Petipa and Ivanov, with music by Tchaikovsky, and produced at the Maryinsky Theatre, starring Pierina Legnani and Pavel (also known as Paul) Gerdt.

Swan Lake is a four-act ballet. Acts I and III, both set in the palace, were choreographed by Petipa; acts II and IV, the "white" acts, were created by Ivanov. The ballet tells the story of Princess Odette, who has been turned into a swan by the magician von Rothbart. At midnight she and her swan companions dance, and she falls in love with a human who is later unfaithful to her.

In act I Prince Siegfried celebrates his 21st birthday. When his mother reminds him of his duty to choose a bride, the unhappy prince leaves the party and goes to the lakeside.

In act II Siegfried meets Odette, the Swan Queen, at the lakeside. He falls in love with her and promises fidelity. They dance a pas de deux to seal their love vows. The White Swan pas de deux symbolizes the purity of Odette's trusting love for Siegfried.

Act III takes place the next evening at a ball in the palace. Von Rothbart appears and introduces Siegfried to Odile, the Black Swan. She is a captivating young woman who looks like Odette. In the Black Swan pas de deux, Siegfried and Odile dance and she bewitches him with her fiery beauty. He asks her to marry him. A vision of Odette appears, and Siegfried realizes he has broken his promise to her and rushes to the lakeside.

In act IV, Siegfried searches for Odette. When he finds her he tells her of his unfaithfulness and asks forgiveness. The ballet has had several endings, both sad and happy. In some versions von Rothbart creates a storm and both lovers drown, or Odette throws herself into the lake and Siegfried follows. In others, Siegfried defeats Rothbart and breaks the spell.

Swan Lake is the prototype of a classical ballet. The dual role of Odette/Odile is challenging for the ballerina, who must be able to portray both good and evil characters. She must have both expressive and technical virtuosity for the dual role. Many shortened versions of the ballet have been created, some combining the second and fourth acts into a one-act version. With its music, story line, and symbolism, Swan Lake is an enduring work of classical ballet as an art form.

Dance Literature

During the second half of the 19th century, social dance instruction books continued to dominate dance literature. Choreographers were still searching for ways to notate dance. Publications included Saint-Léon's La Stéochoréographie or L'art écrire promptement la danse (1852) and later Friedrich Zorn's Grammar of the Art of Dancing. The technical demands of dance had changed vastly from the previous century, so Feuillet notation had become inadequate. Zorn's book, written in German, was translated into English and Russian. His notation used stick figures below musical staffs and drew the dancers from the point of view of the audience.

One of the monumental books of this period was August Bournonville's My Theatre Life, a three-volume memoir published in 1847, 1865, and 1878. Throughout his career, Bournonville wrote articles and essays on the aesthetics and philosophy of the arts. He wanted to be recognized as a man of the theater as well as an intellectual.

Learn more about History of Dance 2nd Edition.

More Excerpts From History of Dance 2nd Edition With Web ResourceSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW

Latest Posts

- How do I integrate nutrition education into PE?

- How does the support of friends and family influence physical activity?

- What makes the Physical Best approach unique?

- Strength training gimmicks . . . or not?

- How do vitamins and minerals support our bodies?

- Why do many people have difficulty losing weight?