Moving from the Comprehensive School Health (CSH) program to the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model

This is an excerpt from Promoting Health and Academic Success 2nd Edition With HKPropel Access by David A. Birch,Donna M. Videto & Hannah P. Catalano.

By David A. Birch, Hannah P. Catalano, Donna M. Videto

Evolution of School Health

Promoting the health of students has historically been recognized as a responsibility of schools. In the early part of the 20th century, a primary focus of school health was the prevention of communicable diseases. The model for school health that was used for most of the 20th century was a three-component model that included health education, the school environment, and health services.

In the late 1980s, to provide direction in addressing the health priorities of school-age children, Diane Allensworth and Lloyd Kolbe, prominent leaders in school health, proposed an eight-component model for health promotion, the Comprehensive School Health (CSH) program. The term “comprehensive” was later replaced by “coordinated” when referring to CSH. The eight CSH components were as follows:

- School health services

- School health education

- School health environment

- Integrated school, family, and community health promotion efforts

- School physical education

- School food service

- School counseling

- School site health promotion programs for faculty and staff

The intent was for CSH to serve not only as a vehicle for promoting the health of students but also as a supporting factor for the promotion of academic success (Allensworth and Kolbe, 1987). Students’ health and academic success are interdependent. Students who face health challenges such as stress, physical and emotional abuse, aggression and violence, safety concerns, hunger, malnourishment, hyperactivity, lack of sleep, vision problems, asthma, and dental health problems often experience academic issues (Basch, 2011; Kolbe, 2019). Research demonstrates a strong relationship between students’ healthy behaviors and academic achievement as indicated by standardized test scores, graduation rates, and attendance (CDC, 2022b).

The importance of CSH was emphasized through the publication of a special issue of the Journal of School Health (JOSH) in December 1987. Allensworth and Kolbe coauthored the introductory article in the issue, which presented an overview of the new approach to school health and its interdependence with education (Allensworth and Kolbe, 1987). National leaders in the relevant areas were invited to write articles related to each of the eight components.

As CSH moved through the 1990s, the term comprehensive was replaced by coordinated when referring to CSH. Although CSH received increased national recognition in the late 1980s and funding was provided by the Division of Adolescent and School Health (DASH) of the CDC to selected state departments of education and departments of health, implementation in local school districts was less than optimal (Basch, 2011). McKenzie and Richmond (1998) described this dilemma, stating, “The promise of a Coordinated School Health program thus far outshines its practice” (p. 10). More than 10 years later, Basch (2011) provided another perspective by stating, “Though rhetorical support is increasing, school health is currently not a central part of the fundamental mission of schools in America, nor has it been well integrated into the broader national strategy to reduce the gaps in educational opportunity and outcomes” (p. 595). One possible reason for this lack of acceptance was that educators and other stakeholders viewed CSH as a health program focused only on health outcomes rather than an initiative that would also contribute to improved academic outcomes (Allensworth, 2015). Further information related to CSH is presented in chapter 2.

Moving From CSH to WSCC

ASCD, a leading education professional organization, has been a leader in the 21st century in illuminating the connection between health and education. In 2007, ASCD implemented its Whole Child approach. This approach focuses on the long-term development and success of children rather than only on a narrowly defined version of academic achievement. An important element of the approach is the inclusion of five Whole Child tenets: healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged. These tenets were identified as essential for students’ health and learning (ASCD, 2014). The Whole Child approach is addressed in more detail in chapter 3.

In 2014, building on both the ASCD Whole Child approach and the original eight-component CSH model, ASCD and the CDC collaborated on the development of a new school health model called the WSCC model (ASCD, 2014). The development of the new model involved a core group that provided leadership to the project, a consultation group that developed documents and frameworks related to the new model, and a review group that periodically reviewed and provided feedback on the work of the consultation group. Members of the three groups were selected because of their roles as leaders in both education and health (Lewallen et al., 2015). The WSCC model was introduced at two national conferences, the ASCD conference in Los Angeles in March 2014 and the Society for Public Health Education (SOPHE) conference in Baltimore also in March 2014 (Birch and Videto, 2015). WSCC incorporates and builds on both CSH and the ASCD Whole Child approach. The model is designed to promote alignment, integration, and collaboration between education and health and is intended to enhance health outcomes and academic success (ASCD, 2014).

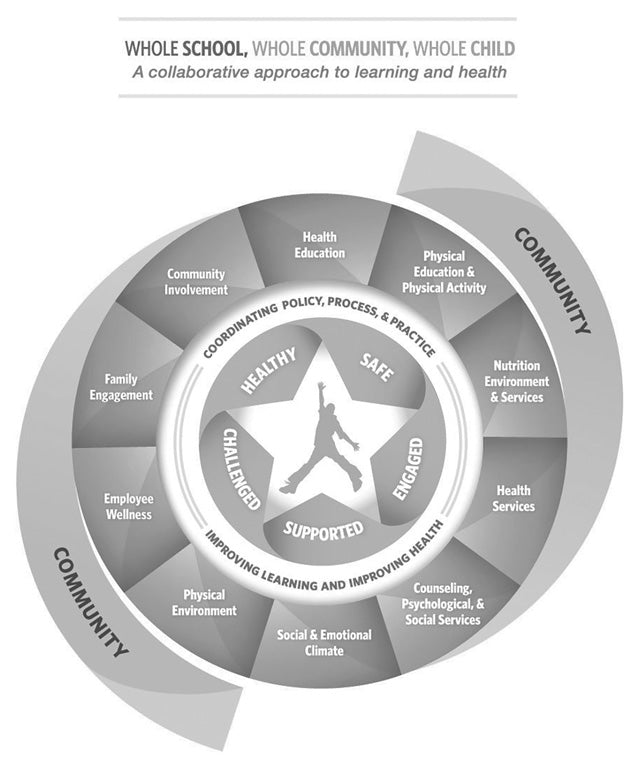

A diagrammatic representation of the overall WSCC model is presented in figure 1.1. As depicted in the figure, the child is the focal point of the model and is placed at the center surrounded by the five Whole Child tenets. Coordinating policy, process, and practice are placed in a ring around the tenets, which signifies the intention of the model to promote both learning and health. An even larger ring consisting of 10 school components surrounds the child, the tenets, and the coordination ring. The 10 components serve as focal points for the full range of learning and health support systems for each child, in each school, in each community. The community is on the periphery of the model, which demonstrates that although the school may be the focal point, it remains a reflection of its community and requires community input, resources, and collaboration to support students. Essentially, school issues are community issues, and community issues are often school issues.

Reprinted from ASCD, Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child: A Collaborative Approach to Learning and Health (2014).

An important aspect of WSCC is the expansion from eight CSH components to 10 WSCC components. One original component, healthy and safe school environment, was expanded into two separate components: physical environment and social and emotional climate. Another original component, family and community involvement, was expanded into two components: community involvement and family engagement (ASCD, 2014). The evolution of the three school health models is presented in chapter 2 (see figure 2.1).

Since its introduction in 2014, WSCC has received considerable attention at the state and national levels (King and Lederer, 2019). Because it was developed through collaboration between an education association (ASCD) and a health organization (the CDC), WSCC appears to have more local, state, and national recognition than CSH as both an education model and a health model among schools and organizational stakeholders. In a 2015 special issue of JOSH focused on WSCC, Lewallen and colleagues (2015) suggested that the inclusion of both education and health in the model provides a framework for schools to both promote academic achievement and address the numerous individual, school, and community factors that affect students’ health.

More Excerpts From Promoting Health and Academic Success 2nd Edition With HKPropel AccessSHOP

Get the latest insights with regular newsletters, plus periodic product information and special insider offers.

JOIN NOW